“Beautiful sisters,” the barista complimented, handing us our matching black coffees.

“She’s my mother,” I corrected, smiling at her deep blue eyes, vanilla-colored hair and tiny frame. I loved when people thought I looked like her.

“Good genes,” he said.

He couldn’t see the long ragged scar hidden beneath her sundress, the splinters along my own hips, or the secret pain we shared with just each other.

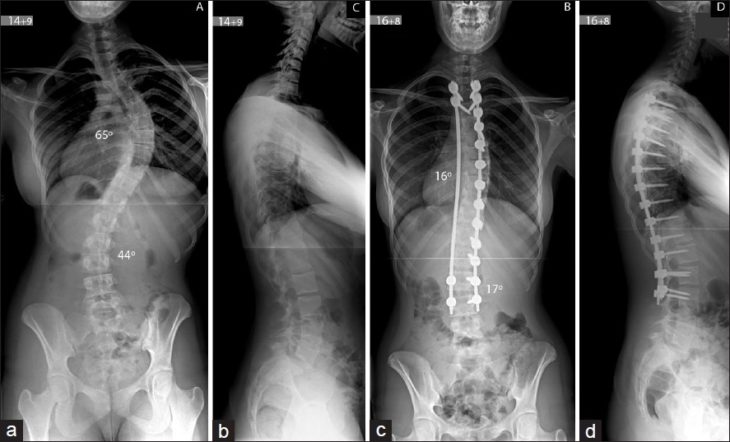

When my mother was the same age, they had no choice but to fuse her spine together, inserting a metal Herrington rod in her back. The surgery left her bed ridden in a body cast for six months. She seemed to understand my anger. Our normal mother and daughter symbiosis became even more intertwined because of Scoliosis.

My mother had been my sole support and mirror for as long as I could remember. I’d deferred to her to make my decisions, having never learned to trust myself. Even at 25-years-old, I wasn’t ready to let go and face the independence of adulthood—graduate school, career and marriage.

Source: Scoliosis SOS Clinic

Growing up, my mother told me she’d thought she was a freak. When my spinal deformity was diagnosed at 11-years-old, there were two of us connected by humiliation.

I stood in the Gap dressing room, tall and lanky in white Hanes underwear, as my mother strapped the enormous, plastic brace around my curved back. “Suck in,” she said, securing the casting from behind with thick Velcro bands. It took all of her body weight to fasten the brace shut around me. It covered my torso from just under my breasts to above my thighs. As I looked down at my expanded body and protruding plastic hips, I couldn’t breathe.

“Try these ones.” My mother held up a pair of loose-fitting overalls in an adult size 6.

At 5 feet tall, I was well under 100 pounds. My soccer coach had nicknamed me Olive Oyl because I had long dark hair and a thin frame like Popeye’s cartoon crush. But the pants wouldn’t squeeze over my new artificial body, the one I was now confined to for 23 hours a day. My vertebra was quickly twisting into the Adolescent Scoliosis my orthopedic surgeon father had first spotted on the beach, threatening to leave me looking like Quasimodo and crushing my internal organs.

Stuck in my rock hard shell, unable to get out on my own, my mother brushed my hair out of my eyes murmuring, “Beautiful face.” I shoved her off me. “It’s your fault,” I screamed, tears running down my cheeks.

She stared at the concrete floor and crossed her thin arms, helpless. She must have known what was in store for me—a distorted reflection. I’m not sure it’s possible to spend puberty covered in plastic and see your body as anything except big. At least it wasn’t possible for me. In that moment, I wanted to hate her for giving me the gene that was ruining everything, but as she wrapped her arms around me, I could feel her crying.

When my mother was the same age, they had no choice but to fuse her spine together, inserting a metal Herrington rod in her back. The surgery left her bedridden in a body cast for six months. My mother lived in a small ward crammed with 30 other children. As the cold wet casting hardened in layers around her, she was abandoned in a dark room shivering and screaming so the others wouldn’t hear her.

When I got my first period, a month after I went into the brace, my mother tucked me into bed, and shared her war stories with me. She was the only person in my world who’d lived through this embarrassment. “I got mine in my body cast using a bedpan,” she told me.

Source: Hackensack Meridian Health

Every time she shared a piece of her private world I felt terrible for complaining about mine. But she seemed to understand my anger. Our normal mother and daughter symbiosis became even more intertwined because of Scoliosis.

My clunky brace smelled like pre-teen sweat from sticky summer days spent outside. It left bruises and gashes along my underdeveloped hips, splinters in my soft skin. At night, as I chanted the Torah portion in preparation for my Bat Mitzvah, my mother soaked my sores in rubbing alcohol so they wouldn’t leave permanent scars. It burned as she held white cotton balls against my pale skin. No amount of rubbing alcohol could prevent the scars forming beneath the surface.

I started hiding the brace under her hand-knit blankets in my closet. In the winter, covered in a bulky North Face ski jacket, I’d leave it at home while I went to school, hoping my curve would stay the same and I’d prove I didn’t need the brace. When it got worse, the doctor lined the plastic with metal “enforcers” that protruded from my stomach like Pez dispensers.

Despite my defiance, my mother attempted to ease my pain, perhaps wishing she could rewrite her own history. For my first school dance, she gave me two hours out of the brace, instead of my usual 60 minutes, so I wouldn’t have to dance with boys in my solid casing. “Promise I don’t look big,” I begged her. When I looked at my reflection, all I saw was wide. I became reliant on my mother as my mirror, to tell me what was really there, even after the brace came off.

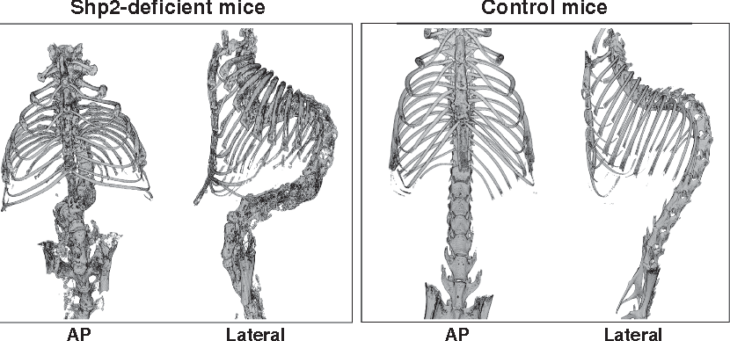

Source: Semantic Scholar

“You can’t look big if you aren’t. It’s only the brace,” she replied, pinning my long dark hair off my angular face.

While the rest of my world looked at my awkward appearance with pity, my mother treated me with the truth even when it wasn’t nice. “That shirt is too small. I’m sorry to say it. But it just doesn’t fit over that thing,” she said, sending me back upstairs to change. My mother was the only person I trusted to be honest with me.

In front of my friends, I pretended it wasn’t there. At her suggestion, I developed a confident coating to protect myself from the undercurrent of middle school ridicule that loomed around me. When I overheard my peers referring to me as the arcade game Feed Big Bertha, I relied solely on my mother for emotional support.

“Don’t let them see you’re hurting or it will be worse. We are giving you the gift of great posture. Use it,” she advised.

As long as she loved me, it didn’t matter that I couldn’t stand myself.

I spent three years in the brace, before I stopped growing at 5’7 and 13-years-old. Even though the doctors had straightened me out, I was uncomfortable with my body and in need of my mother’s approval. While most teenagers rebelled, exploring their own style and identity, I relied on Mom’s blessings, sometimes blindly. I majored in English instead of Theater because she thought it was practical. I didn’t wear red—she said it was for prostitutes. Even now, I’ve never tried crème brule because she once told me I’d hate it.

Even after college, Mom continued to act as my anchor. I called her incessantly for her opinion on my choice of outfit, my weekly grocery list and my own feelings. “Is it OK that I am upset, or am I being ridiculous?” I asked, needing her to gauge my reactions.

My mother was the last brace I hadn’t taken off.

The day I realized I was willing to let go of Mom, I was waiting for her to tell me if I should get back together with my boyfriend of three years. She’d listened to every one of my tearful thoughts during our month-long breakup; traveled between Boston and New York all summer to hold my head up; moved my belongings out of the apartment we had lived in together, and into a downtown studio she’d selected. For 13 years, I’d relied on her to gauge reality and tell me what was good for me. But when I called her earlier that day, she’d drawn the line. “I don’t know what to do,” I sighed into the receiver.

Source: Indian J Orthop

“This is your relationship. I can’t decide for you. I am sorry, but I can’t.”

“Why not?!” I screamed.

“Because I love you,” she yelled.

I knew she did. I could hear it in her voice—the pain of wanting to pick for me, of wishing she could take the hurt away, but knowing loving me really meant forcing me to decide alone, even when I was desperate to hold on to her.

As I stood up and folded my tattered blanket, ready to face myself, the phone rang. For the first time, I ignored her, out of love.

Original by Alyson Gerber