A chat with Roxana Shirazi is a delight. She’s thoughtful, articulate and you just want to steal that lovely, soft-spoken British accent out of her throat and run off with it. So it’s pretty easy to forget this London-based Iranian author has written the ultimate rock ‘n’ roll memoir about insatiable sex drives, peeing on rock stars, and cunnilingus with groupies.

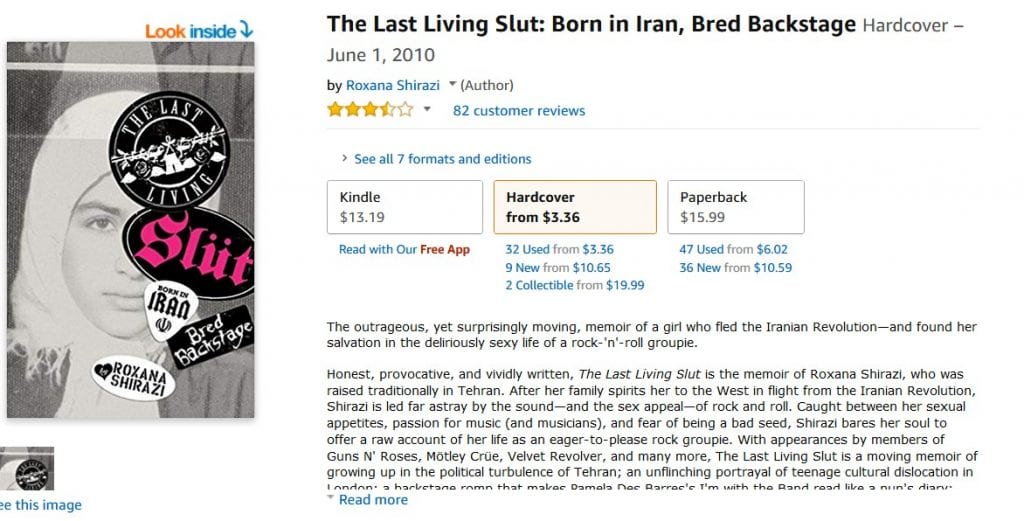

The Last Living Slut: Born In Iran, Bred Backstage is one of the craziest memoirs I’ve ever read and not just for the stunning narrative arc. Although she writes about childhood growing up in Tehran, Iran, during the Iranian Revolution, and the sexual and physical abuse she suffers from her friends and family, Roxana also gives us a peek into a balls-out, X-rated life most of us couldn’t imagine. Co-published by Neil Strauss, author of The Game, and Anthony Bozza, her book is also about becoming a teenage belly dancer at underground London clubs, then a rock ‘n’ roll scenester who beds her rock star idols — guys from Guns N’ Roses and Buckcherry, to name just a few.

It’s funny. It’s gross. And it’s unlike any memoir I’ve ever read. So I called up the woman who carries around a vibrator in her purse and asked Roxana Shirazi to talk about growing up in a fundamentalist Islamic culture, her abortion, female jealousy, and the meaning of the word “slut.”

You were born in Iran before the revolution. What was your upbringing in Tehran like?

I was born just before the revolution, so it was a very chaotic childhood. But at the same time I grew up within a very loving family. Persian culture is very rich, so you’re always with your aunts and uncles and grandparents and everyone will have dinner together. It’s kind of like Italian culture, I suppose. It’s very rich in the sense that there’s lots of family and love and dinner parties and constantly kids running about, making friends. It’s a good, warm community. My childhood was a mixture of the rich Persian culture and the start of a really big political upheaval in Iran, which was actually worsened by the fact that all my family were political activists and prisoners. Me and my mother would make daily visits to prison — like, we’d go and visit my uncles who were imprisoned because of their political beliefs. Constantly, there were soldiers in the neighborhood and secret police raiding homes. There was fear, an atmosphere of fear. So I was brought up amidst these two dichotomies: one a loving family, but one being the constant fear that something would happen to them.

When you were 10, your parents made you leave Iran to go to school in England.

My parents thought it would be a good idea to get me away from the war. There was a war going on and [Iran was] getting bombed every night. They thought, “Well, it’s not a good environment for a child to be in.” The Islamic Revolution had just begun, so women were constantly being punished and tortured for even the slightest thing, like wearing nail polish. My mom thought it was a very bad place for a female to be in. It was absolutely oppressive for a female to be in that environment. So she thought it was a good idea for me to be sent over to England to live with my aunt and uncle. My grandmother accompanied me.

But even though England was a more free society for females, you encountered a lot of racism there as someone from the Middle East.

I was 10. I thought England was like “Mary Poppins” where everything was lovely and shiny and bright. [But] this school was totally white. They’d never seen anybody from a different culture. There was constant racial bullying. Every day, I was in such shock because I didn’t understand why me being from a different country would bring in such horrible bullying, such violence. I just didn’t understand the concept of what that meant. All I knew was every day I was called lots of names or I’d find dog feces in my desk or be constantly teased for being dark. As a child, a 10- or 11-year-old, it was incredibly tough. I don’t want to, like, feel sorry for myself but I really did find it incredibly scary. I really didn’t know how to cope with it. I didn’t have my mother with me. I think, if I’m honest, I started to have an inferiority complex maybe and have low self-esteem throughout my teenage years. Bullying, for all children, leaves a huge mark even later on in life.

England is where you got into rock ‘n’ roll music, though.

Well, the first band I listened to was Guns N’ Roses when I was about 12. For me it was the epitome of the bad boys. The music was just all about girls and drugs and alcohol. It was something I wasn’t sure about. I liked the beat of it, the rhythm of it and the feel of it, but I thought that that was something I couldn’t identify with. So I stuck to Wham! and Duran Duran and all these English pop bands. But secretly I loved these bad boys in these videos. I loved to watch Motley Crue videos and all these American bad boys with long hair and tattoos really appealed to me. The music was so raw. I was always into [the music], but it wasn’t until later in my life that I got into the lifestyle as well. Or maybe I had a bit more confidence that I could belong in that world. But I got into the whole [rock ‘n’ roll] lifestyle.

You got into stripping when you were a youngster, too

I’ve always had, like, two lives. Throughout my teenage life, I was beaten a lot [by my stepfather] and I ran away. So I had this secret life of dancing and strip clubs when I was 16. Then I moved away from home and had my own place eventually. I graduated and I started to be a belly dancer at these underground Arab/Indian men’s clubs where there were lots of girls dancing or bellydancing. A very interesting world, but I wouldn’t recommend it! (laughs) Quite sleazy! It’s very sweaty and there’s dirty men … (laughs)

You were also studying women’s issues at Bath Spa University in England.

Once again, a double life. (laughs) I was studying by day: being very academic, writing lots, speaking at women’s conferences about gender issues. But [I was] being a completely wild, different person at night and putting on different clothes and being a different self.

I’m curious why you embrace the label of “slut,” but you shun the label of “groupie” — which is how most people would refer to your relationship to these rock musicians and bands.

I don’t like labels at all. After studying at university — studying philosophy, Michel Foucault — I came to realize that I’d like to deconstruct socially understood norms. I like to take apart labels. Labels automatically put you in a type of behavior and codes, define certain codes of behavior. Even “feminist,” it instantly puts you in a label or a category or something that could have negative connotations. I like to say I’m a human being: I like to say I’m very sexually wild and open, but I’m also very academic and I’m very into my Iranian culture. I just don’t like to put it in one category. I think all of us human beings are very complex.

In terms of the word “groupie,” well, I’m just too wild to be a groupie. It’s not that I don’t like it; it’s just not accurate, the word. I think “groupie” means someone who is there to provide inspiration, be a muse, or provide some sort of service to a rock star. I like the rock star to provide me with service and inspiration. I like to go to gigs and find someone to get me off. I’m not just there for them; I’m there for me.

And with “slut,” I try to talk about the word and what it means in society in negative connotations [in the book]. It’s so negative, but it just means someone who has lots of sexual partners. What, does that make you a bad human being?

Throughout a lot of the book, you have sex with rock ‘n’ roll guys just because it’s sexually fulfilling for you and you didn’t care about finding emotional fulfillment from them. You got into trouble with yourself, though, when you fell in love.

It was a difficult balance to have. On the one hand, I’m quite sexually open [and] sometimes I just did experiences for the thrill and to push boundaries and to push the boundaries of these rock stars. And it was fun, but at times it was not so fun because I did it as an act of numbing myself to a really bad point in my life. There was a point where I had just had an abortion. That, to me, wasn’t fun. I had gone to see Buckcherry and it was purely, purely to just close my eyes to everything that was happening to me. Rock ‘n’ roll was the only thing that I knew; it was like a drug. A drug addict might do drugs to numb the pain of their problems and forget it. Rock ‘n’ roll was my drug in the sense that when I was feeling down and bad, I would have sex with these rock stars. The abortion was during a bad time. But then there’s so many good, fun times. Some of it gave me a huge kick, when rock stars would cry, ‘Oh, no, I can’t do that! That’s too much for me!’ (laughs) And I’d be, like, ‘Come on, p***y, do it!’ Sometimes it was great fun!

It seems like the rockers saw you as a “girl’s guy,” but I would have thought at least some people would be judgmental of a woman who was sleeping with everybody on the tour bus.

I would say the majority of the men in rock ‘n’ roll are really cool. The Buckcherry guys thought I was awesome. The Motley Crue guys thought I was awesome. It was actually a good experience because they got what I was about. Honestly, I can’t think of anyone who has judged me. (pauses) Girls have. Not the guys in the bands, but girls are much worse than the guys. The girls in the rock scene are horrible. Women are their own worst enemies, really. They really can be so vicious sometimes. The women I encountered on the rock scene were [sometimes] older women who just hated the fact that I would hang out with a band that they loved and they couldn’t. Women felt uncomfortable with another woman being quite sexually open. While I don’t personally, I have to try and figure out why that is. A lot of them are very supportive and cool, but I think a lot of women call other women “whores” and “sluts” if they see other women at a gig wearing slutty clothing. They hate that. It’s a jealousy thing.

Are these rockers OK with you writing about all the sex you had with all of them in the book?

I’ve had good responses from some of them and it’s been very, very nice and supportive. But I haven’t talk to all of them yet.

Did you ever question yourself whether you should write the book as graphically sexual as it was? I mean, I’ve read some dirty books before and this one is really graphic!

Oh yeah, totally! There were things I couldn’t include. Then my editor, Neil Strauss, who has been very supportive of me and my book, said, “You can’t gloss anything over. You have to paint a picture like a documentary-maker: the good, the bad, the ugly about everything. If you can describe sexual abuse or getting beaten, you also have to be real with the sexual stuff.”

One of the more serious parts of the book, however, is when Dizzy Reed from Guns N’ Roses accidentally got you pregnant and pressured you into having an abortion, even though you two were in love.

Horrible. It was very unpleasant to write about. I couldn’t even do it without crying. I’d write and then put it away. It was just horrible. I can’t even read it now. There was no closure. I still don’t feel I’ve had closure from that because I’ve never talked to Dizzy about it.

You talked about the sexual abuse you experienced as a kid in your interview with Details magazine and you commented how people sometimes assume strippers or other very sexual women must be acting that way because they were abused. I loved this one line that you said: “I hate that there’s got to be a reason if women are sexual.”

I read the Jenna Jameson book (How To Make Love Like A Porn Star: A Cautionary Tale) and I read that she was gang-raped as a 16-year-old and my thoughts were immediately, “People are going to say it’s why she became a porn star.” But equally I have so many friends that told me when they were younger that they masturbated [and] they played with themselves. Nothing bad happened to them, they had a loving family, a great childhood. Human beings are very complex.

I have had therapy for [the sexual abuse] and analyzed it in detail. But I honestly can say I don’t think it’s because I was abused as a child that I’m sexual. I know the damages that did to me: it’s nothing to do with the sexual things, the damage it did to me was the men I looked for to love me to compensate for the love that I never got from my father. That was totally more hurtful to me as a child, the lack of a child. But the sexual abuse thing — and I’ve really been healed over it by therapy and things like that — I really think in this society that there’s got to be a reason for a woman to be sexual. We never question mention. We think they’re just being studs and Casanovas and “oh, yeah, he’s just being a guy!” A woman, there’s this problem area. What is the reason? Why is she sexual? It’s just a crime to think like that because women are human beings as well as men. We’re sexual. We’re sensual beings. I just think people should just leave us alone. Let us be human beings for God’s sake without stigmas and labels. It’s so irritating.

Did you read the Newsweek review of your book? It was exceedingly nasty, comparing the book to “diary entries” and accusing you of being “exploitative” of your backstage pass experiences. But what I really disliked was how the Newsweek review criticized the way you wrote about growing up in a Muslim culture: “Shirazi goes so far out of her way to exploit the Iran angle — selecting a picture of herself in a headscarf for the cover; doing a promo photo shoot in porn-star poses and a black veil — that we expect her to make some coherent statement on Islam, gender, and sexuality. But she never does.” I think, though, that just because you were raised in Iran during the Islamic Revolution doesn’t mean it’s your responsibility to make some grand statement about Islam and gender.

My family are anti-religion. It’s in my book. Whoever wrote that must not have read my book. It states clearly in my book that my family went to prison and were in danger in the Islamic Republic of Iran because they were anti-Islam. It states clearly why my parents were politically active. If anyone had half a brain, they would know if anyone is so hunted down in that government it is because they’re against [the religion].

I didn’t think my book was about Islam! It was about my life.

Original by Jessica Wakeman