Another school shooting. This time it took place at Marysville-Pilchuck High School in Washington state. Fourteen-year-old high school freshman Jaylen Fryberg, pulled a gun out during lunch and began shooting, killing two 14-year-old girls, and severely wounding three other students before dying from a self-inflicted gun shot. Like with each school shooting before this one, we all sit back and wonder… why? How?

We can talk about guns as the root of all evil in these instances (Fryberg used a gun that was legally purchased) — and in fact, we should be shouting about the ease of access to guns in this country — but it’s not that simple. Because there’s more to it than just guns. Reports are slowly coming in that Fryberg may have targeted particular students at his school over a recent breakup. While we may never truly know his motivation, many are starting to piece together information gathered from fellow students and Fryberg’s own social media accounts. A student at Marysville-Pilchuk High School told the Seattle Times that Fryberg was “angry about a romantic relationship he was involved in, and that the girl was one of the people shot, according to a student. Another student spoke about Fryberg and one of the victims, telling Reuters that she “heard he asked her out and she rebuffed him and was with his cousin. The student boils it down: “It was a fight over a girl.”

A day after the shooting, my friend (and Frisky contributor) Veronica Arreola posted on her Facebook wall a challenge to all who were listening:

“Instead of a national discussion about guns, let’s have one about how we raise boys to think a girl rejecting him is the worst thing in the world [and] he must resort to violence to restore his masculinity. How about that?”

Veronica’s post resonated me. While I definitely think we can talk about both guns and the concept of masculinity simultaneously, the latter tends to get brushed to the side in the aftermath of similar shootings. But, when 97 percent of school shooters are male, we must talk about this. I started jotting down thoughts on toxic masculinity and how boys are continuously inundated with patriarchal messages that sell the idea that they’re entitled to attention from girls and women. I thought about my own son, almost eight years old, and how he is already one charming fellow. I worry about walking that line between helping to build up a sense of self-confidence in him, without also offering the message that he should get everything that he wants, consequences be damned. I try to instill in him that people are not property and that while friendships — and in the future, relationships — can be complicated to navigate at times, he isn’t owed anything by anyone (and vice versa).

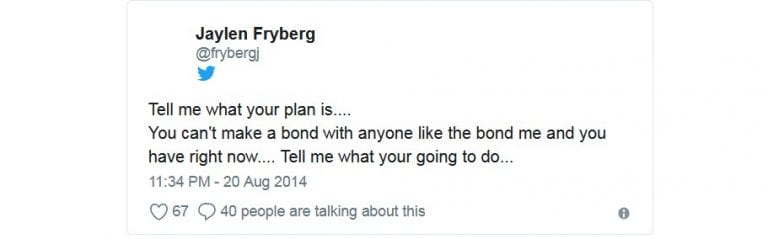

I’m doing my damndest to set that framework, because society tells a different story. One where men are the heroes, the knights in shining armor, the ones who get the girl, at any expense. However, when they’re rejected, are young men equipped to handle it in the face of all the masculine expectations that are out there? Fryberg’s Twitter feed leading up to the shooting makes me think we have a long way to go when it comes to “boys being boys.” After one of the 14-year-old girl victims reportedly broke up with Fryberg to date his cousin (who Fryberg also targeted), he issued a series of pained tweets.

His tweets leading up to the shooting gave some insight, showing a young man who was clearly hurting, but didn’t know how to express or share that pain.

But what happens when we dare to even bring up the concept of toxic masculinity? On Friday, pop culture critic Anita Sarkeesian went on Twitter to call out the notion of toxic masculinity in relation to the shooting, and the response only solidified her point. Sarkeesian received all manner of explicit, detailed threats, including rape, death and calls to kill herself. The more mild mannered tweets explained why she was getting threats, insinuating that it was her fault for provoking the “haters.”

But what happens when we dare to even bring up the concept of toxic masculinity? On Friday, pop culture critic Anita Sarkeesian went on Twitter to call out the notion of toxic masculinity in relation to the shooting, and the response only solidified her point. Sarkeesian received all manner of explicit, detailed threats, including rape, death and calls to kill herself. The more mild mannered tweets explained why she was getting threats, insinuating that it was her fault for provoking the “haters.”

If we can’t even talk about the problem with toxic masculinity — and notice, nobody is saying the problem with men — without it rearing its ugly head full of entitlement and violent rhetoric, how can we even go about figuring out solutions for these devastating and all too frequent shootings?

Original by Avital Norman Nathman