“You guys know about vampires? … You know, vampires have no reflections in a mirror? There’s this idea that monsters don’t have reflections in a mirror. And what I’ve always thought isn’t that monsters don’t have reflections in a mirror. It’s that if you want to make a human being into a monster, deny them, at the cultural level, any reflection of themselves. And growing up, I felt like a monster in some ways. I didn’t see myself reflected at all.” — Junot Díaz

As a kid, I never tried to sneak out of the house. It’s not that I was a stickler for the rules (sorry, Mom) — it’s just that all the wonders I could ever want to explore didn’t exist outside the confines of my home. They were waiting for me when I woke up each morning, tucked neatly into the hallway bookshelves whose ever-expanding ranks housed J.K. Rowling, Leo Tolstoy, Judy Blume, and Sarah Dessen.

Source: NPR

I spent hours hiding away in my room, staying up well past my bedtime with a flashlight under the covers that probably ruined my eyesight. I read in the car, in the bathroom, in class, anywhere I could find words to digest. I read at other people’s houses, hidden away in a bedroom, stairwell, or closet where I thought no one would interrupt me and The Babysitter’s Club. When my mom would tell me to go into the backyard and play “like a normal kid,” I’d make up excuses to come back inside and grab just a glimpse of the precious text I’d left indoors. Did she really think I needed to use the bathroom every 10 minutes? Probably not, but I didn’t care. I needed to finish the chapter. It was that deep.

Books were (and still are) my way of understanding the world. When I felt like being a girl and being a nerd didn’t make sense in the same body, Hermione Granger was there to teach me better. When awkward middle school crushes threatened to overtake all my cognitive functions, Eragon flew me off on fantastical journeys that stretched my brain further than a braces-filled conversation with any boy ever could.

Source: NOW Magazine

But devoted as I was to the universes hiding between the covers of my favorite books, I couldn’t help but start to wonder why I never read about people who looked like me. I didn’t see us at journalism competitions, on TV discussing New York Times bestsellers, or assigned on any syllabi. Did Black writers not exist? Or worse yet, were Black people just not worth reading and writing about?

To have the one thing that makes sense to you in this world reject your existence almost entirely is no simple diss. It tells you your stories don’t matter, your voice is better off unused, your problems aren’t real. Or worse yet, that you are the problem.

For a long time, this forced me to reconsider my love affair with literature; unrequited love isn’t really my thing. I spent a long time avoiding books because I didn’t want to be antagonized even in a fantasy realm, to always be the nondescript footnote in someone else’s memoir. It was only after immersing myself in the words of Toni Morrison, Frederick Douglass, Junot Díaz, CLR James, Maya Angelou and other Black authors that I fell back into the warmth of literary intimacy.

Source: YES! Magazine

If we understand that children often form the basis of countless social skills through what they read — abilities to empathize, to imagine others’ complex inner worlds, and to problem solve — what are we doing by denying Black children literary representation of themselves coming to grips with the world around them? Black children, like all humans trying to navigate a world that presents more questions than answers, need blueprints. To move through the various obstacles that will inevitably litter their paths in a world that systematically devalues Blackness, Black children need examples of what it might look like to navigate uncharted waters and succeed.

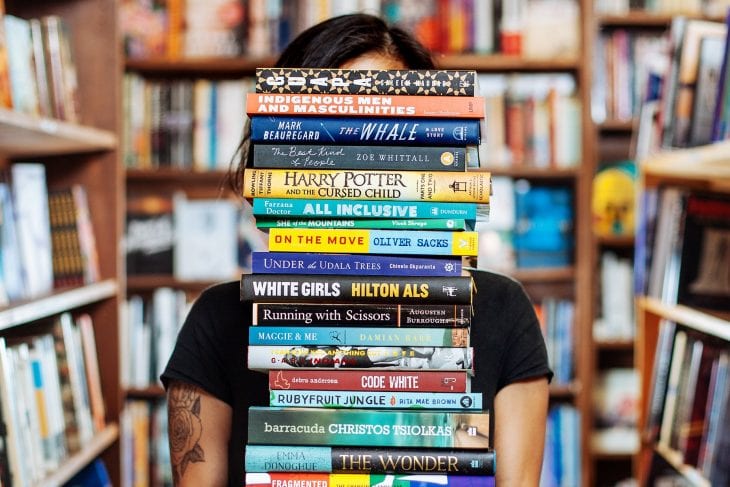

Before he passed away this Wednesday and left a gaping hole in the hearts of readers, prolific author Walter Dean Myers asked in a March op-ed, where are the people of color in children’s books? Myers noted that of the “3,200 children’s books published in 2013, just 93 were about black people, according to a study by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin.”

Myers’ books met black children on their own turf and didn’t demand we stretch ourselves across a Herculean literary gap not of our making. Myers didn’t ask that Black children dress ourselves up in unfamiliar skin in order for our concerns to be taken seriously; he simply wrote Black youth who were fully human. And we deserve that: to be seen, to be recognized, to be reflected. We deserve character development, multi-layered plots, struggle and triumph. We deserve to know that our pain and heartbreak are not singular, that we are simply experiencing the deep complexities of the human condition. And we will make it through them.

Source: Of Magic and Madness

Most recently, the #WeNeedDiverseBooks campaign has addressed the glaring disparities in whose narratives are highlighted for and by the publishing world. But the struggle for visibility as people of color subjects doesn’t end with publishing. Indeed, we must commit to publishing authors of color beyond a small subset of “niche” stories — but we must also do the more difficult work of actively integrating their writing into our literary frameworks. We must not stop at stocking bookshelves with diverse authors; we must also fill syllabi, curricula, book clubs, and review sections. We must read Black authors beyond the month of February; we must quote women not only to explain gender, but also to uncover the depth of their humanity.

With the impending return of “Reading Rainbow,” the children’s show that propelled countless young readers from apathy into obsession, we have a new opportunity to show all kids that their stories matter. Representation may not be the answer to every problem a child of color faces in this hostile world, but sometimes it’s enough just to know you’re not a monster.

Original by: Hannah Giorgis