Like most high school kids, I often fell asleep during class when I was bored. But my last two years of high school, it started happening more frequently and I couldn’t control it. At my after-school job at a coffee bar, I would drink ever increasing amounts of coffee to stay awake during the day. Most of my friends couldn’t drink java after 4 p.m. because it would keep them awake through the night. I would fall asleep an hour after drinking three cups.

By my freshman year of college, I was drinking 10 caffeinated beverages a day, but nothing kept the sleepiness and the lethargy at bay. I would oversleep my alarm every morning, much to the growing irritation of my roommates, and run to class if I hadn’t missed it entirely.

Source: Medium

I begin hallucinating as my brain starts to enter dream sleep but my body remains awake. What follows is a deep and irresistible sleep, lasting from two minutes to 20 minutes. If someone tries to wake me up while I am asleep I become totally disoriented. I can’t remember where I am, what day it is, what time it is, and sometimes my own name for several minutes.

In class, I would struggle to stay awake. My dreams would overlap my consciousness and my hand would keep taking notes that, when reread later, made no sense at all. I would often go home and nap for hours, hoping to shake off the feeling of sleepiness. I’d often sleep right through to the next morning. On my worst days, I would sleep for 16 hours.

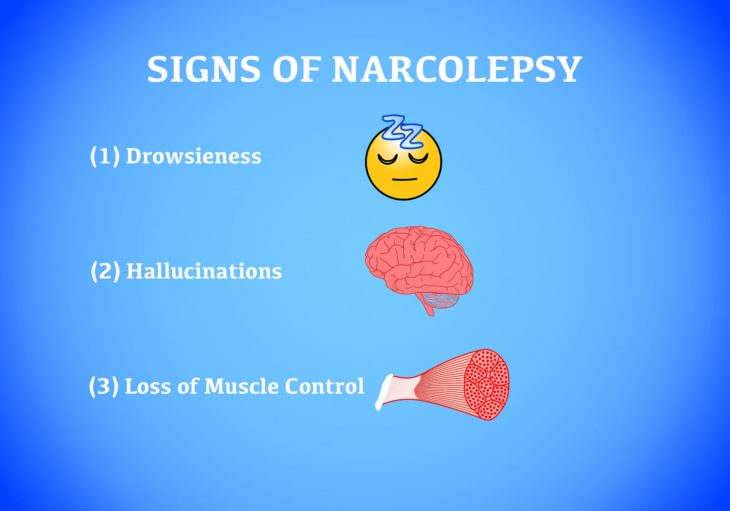

When my doctor told me that I had narcolepsy, I was relieved. By 21, I had spent years going from doctor to doctor with none able to figure out why I couldn’t stay awake and felt as though my brain was always running in slow motion. The previous diagnoses were all over the map—anemia, mono, B-vitamin deficiency, and depression. But no matter what treatments the doctors gave me, the symptoms did not stop. When that first neurologist diagnosed me, it finally gave a name to a problem that had followed me for so long. Looking back, I realize I had symptoms most of my life, but they began to noticeably worsen around the time I turned 16.

In the five years since my diagnosis, I’ve learned to live life on medication. There are a variety of drugs that treat narcolepsy, but none work forever and often doses must be continually raised until the drug in use is no longer effective. I have been lucky enough to be treated with Ritalin relatively successfully, but there are days when it doesn’t work. It’s hard to explain to employers or friends what to expect on those days, but it is nothing like what you have seen in “Deuce Bigalo, Male Gigolo“ or in YouTube clips of the narcoleptic dog.

Source: irnpost.com

No two narcoleptics experience symptoms exactly the same, but for me two symptoms follow me during the day. The first is a feeling of general fatigue. If you have ever had mono or pulled an all-nighter, then you have an idea of what that feels like. It is like seeing everything through a fog: by the time I have figured out what someone said and processed my response, the conversation has moved on. It’s as if my body, and particularly my mind, is running in slow motion while the rest of the world is running at normal speed. The part that most people are more familiar with is the sleeping spells. Unlike what you’ve seen on TV or in movies, I haven’t fallen asleep in the middle of a conversation or during sex, but I have fallen asleep in meetings and on dates.

To me, it feels more like a seizure. I get a five-minute warning before falling completely asleep. During that warning period, I begin hallucinating as my brain starts to enter dream sleep, but my body remains awake. I imagine it’s the same feeling that schizophrenics get—I see things that aren’t happening and my thoughts become a tangled mess. What follows is a deep and irresistible sleep, lasting from two minutes to 20 minutes. If someone tries to wake me up while I’m asleep I become totally disoriented. I can’t remember where I am, what day it is, what time it is and sometimes my own name for several minutes.

It is completely disorienting and scary—for both me and the person unfortunate enough to find me. I once experienced a warning period at work and only had time to sit down and lean against the wall before I fell completely asleep. If I hadn’t sat down, I most likely would have fallen over. One of my coworkers found me and spent several minutes in a panic trying to shake me awake. Despite my warning him that this might happen, he was terrified.

Source: sleepclinicpretoria.co.za

Unfortunately, the symptoms that plague narcoleptics during the day often follow us into the evening as well. Like many narcoleptics, I also experience sleepwalking and night terrors. It’s hard to explain to the people I live with or sleep with what to expect. I have carried on completely lucid conversations with my roommates while fast asleep. I have cooked breakfast and gotten myself ready for school in the morning. I even once wandered around my apartment complex and left my door unlocked when I returned home.

The night terrors are like an extension of that warning period I feel before falling asleep in the day. My brain will have vivid, realistic nightmares while my body is awake. My brain superimposes the nightmare over the reality my open eyes are witnessing. One time, I dreamed burglars were breaking into my bedroom window. Since my body is awake, it is extremely difficult to wake up from the nightmare. During that particular episode my mother sat next to me all night shaking me awake every time I started screaming in terror. When I awoke the next morning I had no recollection of being woken a dozen times the night before. But the exhaustion was written all over my mother’s face. How do you explain that to a roommate or a boyfriend? I still haven’t figured it out.

Source: Medical News Today

When I take my medication, my days without symptoms outnumber my days with them. But I live in fear of losing my health insurance and having to pay for the monthly neurologist visits (because Ritalin is a controlled substance, most states require you to pick up prescriptions from your doctor every month), the daily medication, and the bi-yearly EEG and EKG exams to check for the brain and heart damage that are side effects of the medication that makes living possible for me. Without medication I am legally unable to drive and largely unable to function normally.

So the next time you see someone falling asleep in a meeting, don’t laugh or assume they’re a total slacker. They might not be able to help it.

Original by Anne Olson