If I have to admit it, my interest in fertility rites was probably piqued by watching the god-awful Nicolas Cage remake of “The Wicker Man” on a new friend’s urging last summer. It’s basically a misogynist nightmare of a women’s cooperative run amok off the coast of Washington (of course), which only barely resembles the original 1973 film, in which a pagan cult on an island off the coast of Scotland burns the virgin Sergeant Howie alive as a sacrificial offering to the gods in hopes that it will restore the fertility of the land. The time was ripe in 1973 for a movie like this to come along: The UK and America were both in the middle of the sexual revolution, and horror movies were gaining critical ground. It’s worth noting that horror movies of this particular stripe were of special quality in the late-’60s to mid-’70s: “Rosemary’s Baby” was released in 1968; “The Exorcist” was released in 1973; “The Omen” was released in 1976. We were grappling with our conceptions of morality and whether or not — as the famous 1966 TIME cover questioned us — God was dead. Those were the cultural anxieties these movies were addressing.

All fertility rituals are couched in religion of one sort or another, because all fertility rituals are couched in the belief that humans can appeal to supernatural or at least superhuman forces in order to affect reproductive outcomes — those of humans, those of animals, or those of the earth. And they all come from cultures that are ancient, from the way-back when the fertility of animals and plants was a matter of life or death for humans, and the survival of communities depended on the fertility of humans. The thing is, Easter as a Christian holiday has always seemed, well, odd to me, because the sort of public face of Easter is the pagan accoutrements that the early Christians adopted in order to convert the heathen tribes of Europe — like eggs and bunnies and flowers. Those accoutrements don’t seem have anything to do with the meat of the Christian Easter story, which, despite falling in the same part of the calendar as a lot of fertility holidays and rituals, is not at all about the fertility of the planet or of human beings. All of this got me wondering: What fertility rituals have humans practiced, historically and currently, and what’s the philosophy behind them? Here’s what I found out.

*****

Sacrificial Rituals

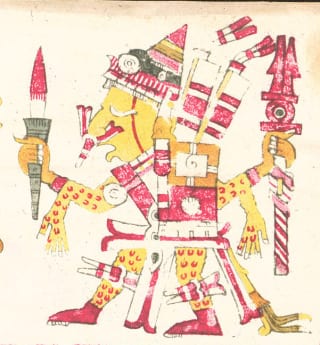

Bertrand Russell notes in The History of Western Philosophy that religions all over the world have practiced human sacrifice “at a certain stage of religious evolution,” and that the Greeks, for example, were still practicing it when Herodotus began recording history. But the society most famous for human sacrifice in the American imagination is, of course, the Aztecs, who had a festival called Tlacaxipehualitzli to honor their fertility god, Xipe Topec (say it with me: Tla-kah-she-peh-hwa-leets-lee, and She-peh Toh-pek). It took place in the capital, Tenochtitlán, at the end of what’s now February, just before the sowing season. Prisoners were sacrificed; their hearts were ripped out, and they were flayed, but that’s only part of the festival. For 20 days following the flaying ceremony, the priests danced through the courtyards and distributed maize cakes and honey tortillas to the people, and the city paid tribute to Xipe Topec with song. According to the Florentine Codex (a research project about Mesoamerican cultures written in the 1500s), the priest gave an invocation to the god on par with the beauty of any hymn I’ve ever heard, asking that the sun (fire) be transformed into water:

…The serpent of fire

Has been transformed into a serpent of quetzal.

The serpent of fire has set me free.

Perhaps I shall vanish,

Perhaps I shall vanish and be destroyed,

I, the tender corn shot.

My heart is green

Like a precious jewel,

But I shall yet see the gold

And shall rejoice if the war chief

Has matured, if he has been born.

On the subject of both fire and sacrifice, we can circle back around to The Wicker Man. It turns out that in Northern European, Germanic pagan religions — “heathen” religions — both Easter (or, in old languages, Eostre or Ostara) and Midsummer (or Litha) were fertility festivals as well as fire festivals. However, the painting of hard-boiled eggs comes from pagan celebrations that also involved balancing the eggs on their ends to symbolize balance and equilibrium, which it’s claimed can only be done on the Spring Equinox, although I’ll have to wait until next year to put that to the test. Eostre is described by Eileen Holland as “a solar festival of fire, light, and fertility.”

Midsummer, or Litha, has better documentation: It takes place on the longest day of the year, during the growing season, and involved bonfires and animal sacrifices. Galina Krasskova describes it as a time when heathens “celebrate the rebirth of their faith,” implying that fertility rituals ask not only for fertility of humans, plants, and animals, but also of faith itself. It makes sense, then, that fire is a feature of some of these pagan fertility rites: Fire, despite our modern conception of it, is a normal part of natural or ecological growth, and controlled burns have been a part of agricultural maintenance basically as long as humans have been growing crops. It clears fields of weeds and harvest residues and prepares the soil for new planting. Or, in other words, it’s used for rebirth.

*****

Menstruation Rituals

Of course, blood was an important part of sacrificial fertility rituals, but other fertility cults, festivals, rites, and rituals venerate menstrual blood and menstrual cycles. (Which seems only right, given what a literal pain they are.) Francis King argues in Sexuality, Magic & Perversion that fertility religions recognize time as cyclical rather than linear and, as Riane Eisler notes in The Chalice and the Blade, “we and our natural environment are all integrally linked.” Menstrual cycles, lunar cycles, and the rotation of the Earth on its axis and its orbit around the sun are all connected. Fertility religions, for instance, carved statuettes of women with pregnant bellies, visible yonis (can we use that word more often? Also, “cunni”?) and huge breasts, painted (as the Venus of Willendorf) in red ochre. Their use of those statuettes, and the red tinting, suggests that they imagined women’s periods and the fertility of plant life as being associated with one another.

This is maybe most vividly illustrated not through a rite of a fertility cult, but through the Hindu festival of Raja Parba, which is meant to honor the three days during which the earth is menstruating. (I cannot think of a cooler way to imagine monsoon season than the earth getting its period.) It welcomes the first rains in the month of Mithuna (roughly mid-June to mid-July in the Gregorian calendar), and it frankly sounds absolutely lovely: All the unmarried girls in the community observe the restrictions placed on menstruating women whether or not they are themselves at that time menstruating; they only eat very nutritious food without salt, they don’t walk barefoot, and they vow to give birth to healthy children in the future. Swings are strung from Banyan trees; the girls spend the three days swinging and singing, and the rest of the community plays games.

It’s a menstruation celebration! And it demonstrates really well the perceived link between the cycles of a woman’s body, women’s child-bearing capacities, the cycles of the moon, the cycle of the seasons, and the cycle of agriculture in non Judeo-Christian religions. Fertility images did work their way into Christian landmarks, though, through images of the Celtic Sheela-na-gig, which are carvings of women displaying their yonis placed on churches built by only nominally Christian (and actually pagan) stoneworkers in England. “Venus fertility figurines” have been discovered by archaeologists that date back to the paleolithic era. Zuni pottery in America, too, are metaphorically breast-shaped, equating the water the pottery carries to mother’s milk. We have, in other words, been equating women’s fertility with the earth’s fertility all over the world for a very long time.

*****

Sex and Marriage Rituals

The major symbolism of many fertility rites was a re-enactment of a heavenly marriage between a god and goddess, and, as Francis King notes, that it was “often directly derived from the act of human copulation.”

In kabbalistic Judaism the Shekinah, which in mainstream Judaism is the presence of God on Earth, is seen instead as the feminine manifestation of God, or the bride of God, whose union created the world, meaning that all life is the result of divine reproduction and divine fertility. That, then, extends to human copulation in marriage, as well.

In Daughters of the Earth, Carolyn Niethammer describes a buffalo-calling rite in the Mandan tribe of what is now North Dakota, during which married women in the tribe would walk with elder men and offer intercourse, which was “considered tantamount to intercourse with a buffalo.” This devotion to the buffalo was thought to bring the herds closer to the villages. The elders didn’t necessarily accept intercourse; instead, they would sometimes offer a prayer for the married couple’s success. By performing the rite, the woman proved to her husband that “she sought his success in hunting and warfare, which would lead to a good home, good health, and plenty of food and clothing.” Beyond being a devotion to the buffalo and a way of praying for the fertility and availability of the buffalo and the earth, then, the buffalo-calling rite was a way of strengthening the marital bond.

Then, of course, there’s jumping-the-broomstick, another pagan tradition that has entered our phraseology as the equivalent of “getting married.” The broomstick is meant to symbolize sexual union — the handle representing a phallus and the brush representing a yoni. Jumping the broomstick at a wedding is an invocation for the couple’s and the community’s fertility. According to Eileen Holland, the image of witches “riding” broomsticks comes from rituals in which pagans “rode” broomsticks through crop fields for the fertility of the land.

Finally, there’s Beltane, a May fertility celebration involving the symbolic marriage of a May Queen and May King, who do a handfasting and jump a broom. Holland describes it as “a fire and fertility festival that celebrates the transformation from maiden to mother through the mystery of sexuality,” and says that it’s a good time to perform the Great Rite, in which:

“The god is invoked into the male witch, the Goddess into the female. […] They make love, worshiping at the altars of each other’s bodies. Power rises above them as the sacred marriage is enacted. Blessings flow from their union. In ancient times, this ritual was the annual duty of the king and high priestess. [… Who were] ensuring the well-being of their people for the year. The rite was believed to activate the fruitfulness of the land, the fertility of humans and animals.”

*****

Easter

What I think I like about these rituals (the parts that don’t involve killing someone or something, anyway) is that the ideas behind them are very applicable to secular life. They’re oriented toward having strong communities, understanding and respecting the power of our bodies, understanding that we’re part of nature, that the things we do affect nature, and that nature’s well-being affects our own. That seems increasingly important as we learn more about how the human impulse to reproduce — the exact thing many of these rituals are attempting to encourage — has, 7 billion people strong, affected the climate, the sea levels, water availability, food availability, and the distribution of resources amongst the global community. That seems like a good thing to reflect upon this weekend, regardless of theology, philosophy, or lack thereof.

[Wiki] [Universal Kabbalah] [Festivals of India] [dishaDiary] [Current Anthropology]Additional Resources:

Neil Baldwin, Legends of the Plumed Serpent: Biography of a Mexican God

Bernardino de Sahagún, The Florentine Codex

Riane Eisler, The Chalice and the Blade: Our History, Our Future

Eileen Holland, The Wicca Handbook

Francis King, Sexuality, Magic & Perversion

Galina Krasskova, Exploring the Northern Tradition

Carolyn Niethammer, Daughters of the Earth

Bertrand Russell, A History of Western Philosophy

Hope Werness, Continuum Encyclopedia of Native Art: Worldview, Symbolism, and Culture in Africa, Oceania, and North America

Original by Rebecca Vipond Brink