In retrospect, it was all inevitable. Not the details, like the time I grew so afraid of using the toilet that I urinated in cereal bowls in my apartment, or the time I collapsed outside a filling station in Sicily and told someone I couldn’t remember how to breathe. Those specific situations weren’t predictable, of course. But looking back, I can see how much sense it makes that I have panic attacks.

I was a nervous little kid. I was shy, frightened of big crowds, averse to meeting strangers, and terrified of speaking in front of class. When I was seven, my wonderful teacher, Mrs. Bonnane, was tasked with delicately explaining to me that the sympathy pains I experienced while reading Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret were not, in fact, menstrual cramps (I was allowed to read whatever I wanted, and apparently manifestos on menarche were what I wanted). I went to see “Jurassic Park” and couldn’t sleep for fear that actual dinosaurs were in my backyard. I worried. A lot. About everything.

Source: Medium

Travel was particularly frightening. There were so many elements out of my control: the speed of the car, the bumpiness of the bus, the size of the plane. Part of my fear was a learned behavior; my dad had certain psychological issues surrounding travel, and when en route to the airport he experienced intense general anxiety that sometimes led to panic attacks and other times led to bouts of strong anger. I learned to hate airports, bus terminals, and train stations, because they made my dad scared or they made him mean.

My mother attempted to control every last detail of every trip in order to stave off my father’s panic or anger, and so her behavior, too, was fraught with anxiety. As she moved through her 20s and 30s, she grew increasingly more prone to depression. During these episodes of deep despair, she would sleep a lot and stay in her room alone. Once in a while she would leave for several hours and not tell anyone where she was going. I would worry that she was never coming back. But she always did.

With a depressive mom and an anxious dad, plus a host of other close relatives with panic attacks, addictions, depression, schizophrenia, and other mental maladies, it was pretty unsurprising when my own unquiet mind began to wail.

One day my mother drove me to school, even though it would make her late for work again. I’d been eating less lately and roaming the house restlessly at odd hours. I refused to get out of bed sometimes, and not because I didn’t like school. I loved ninth grade. I was popular and had an excellent mall wardrobe. School was my jam. But lately I felt a strange fear every morning, and I couldn’t shake it. I looked out the car window at a tree resplendent with fall colors. Suddenly it seemed to stand out in stark relief against the background of the suburban sky, and I had a feeling it was trying to tell me something.

Source: Mindful.org

“I think I need help,” I said, apropos of nothing.

“You’re like me,” she said, because she already knew it anyway.

“I mean, sort of,” I said, looking back out the window. We were passing other trees, but none of them were trying to talk to me.

“We’re going to find you someone really great to talk to,” she said.

And so I started seeing a licensed counselor and social worker once a week after school. I was 14.

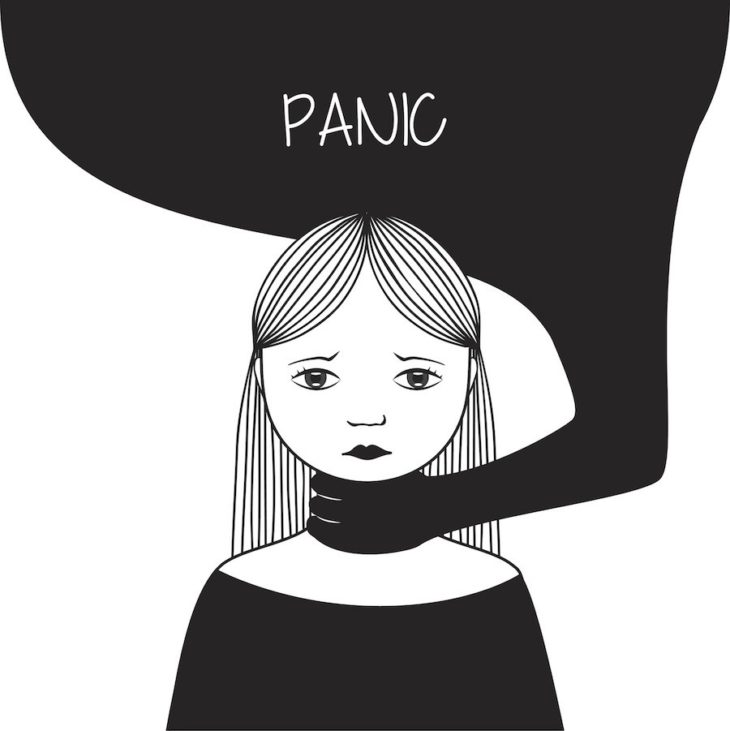

The counselor was awesome, but even she couldn’t stave off the weird chemical tsunami flooding my brain. The panic attacks began in earnest the next year. I’d had them on and off since I was about 10 years old, but I didn’t have a name for them. I’d feel a sudden onset of terror and nausea, accompanied by a pounding heart and a throbbing skull. Sometimes my arms would start to tingle.

“I’m sick!” I’d cry, and I’d go into the bathroom at home or at school and try to throw up. Usually I couldn’t do it, and my friends or teachers or family would say I was just tired or nervous. On the occasions when I was successful, I felt vindicated and relieved. I was sick, see? I was really, really sick. It wasn’t just in my head.

When I was 15, these bouts of fear and nausea started coming all the time. I learned to avoid places that I couldn’t easily escape. I made excuses to get out of school trips. I did everything I could to avoid riding the bus, including feigning all kinds of maladies. When I got frightened, I would go to the bathroom to empty my bladder. I did this so often that a doctor became concerned that I had a disorder of the urinary tract system. She ordered a cytoscopy, a fun adventure in which I lay on a table while a catheter with a teensy camera on it was threaded up through my urethra and into my bladder. Dyed liquid was then pumped into my bladder from the outside. They didn’t knock me out for the procedure, because they wanted me to tell them when my bladder felt full. It hurt, bad. I don’t remember any anesthesia. I had a rip-roaring panic attack right there on the table, sobbing and asking for my mother, who promptly entered the room dressed in one of those fetching lead suits people have to wear around x-ray machines.

“It’s going to be OK,” she said. “I’m here.”

But it wasn’t OK, not really. For the next two days, it burned like fire when I pissed. And when the test results came back fine, I was terribly disappointed. If I didn’t have some actual physical problem, then the frequent-peeing thing must be because I was nervous, like a scared dog. And that was crazy.

Soon, it got so bad that even my dad, a man who resisted taking aspirin, agreed that a trip to the doctor was necessary. The pediatrician put me on Paxil, which didn’t help, and the panic attacks and depressive episodes increased over the next several years. I was afraid that if I told anyone that the drug didn’t work, they’d say, “Well, then you’re really beyond a cure. Time to lock you up!” The only real effect Paxil had was robbing me of the ability to achieve orgasm from ages 16 through 21. No wonder I stayed a virgin for so freaking long.

Source: University of Nottingham Blogs

By the time I was 21, anxiety ran so rampant through my life that I had an honest-to-goodness, old-fashioned, real-deal nervous breakdown.

And then I got really, really depressed. I stopped eating. I stopped bathing. I started pissing in bowls that I kept near my bed so that I wouldn’t have to go to the toilet. Even the bathroom, my longtime refuge, had become frightening and inhospitable. I thought about killing myself. I even talked about it, one day, to my best friend. She told my other best friend (why stop at one bestie?) who called my parents, who brought me home. And that’s when I started to get better for real.

That was 8 years ago. Inexplicably, I’m now a stand-up comedian and a radio talk show host. Now I’m going to turn the weird, wild tale of my breakdown and recovery—a story I’ve told on stages around the U.S.—into an actual book. You know, like Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret, except with more selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. That story is too long to recount here, so you should probably read the book one day and then tell everybody you know to buy it, especially if your name is Oprah. Spoiler alert: I got better. Mostly.

Because you see, I still have panic attacks. A few months ago, I awoke from a dead sleep and bolted upright beside my boyfriend.

“What’s going on?” he mumbled into the pillow.

“I’m having a panic attack,” I said, a little incredulously. I’m a comedian, and I’ve made fun of my own panic attacks so many times in front of so many people that I’m always surprised by the way the attacks still scare the crap out of me. But here’s the great part: They don’t put a stop to my entire life anymore. It sucks while it’s happening, but I trust that, as my grandmother always told me, “This too shall pass.” Odd as it sounds, I no longer panic about my panic.

“What should I do?” my boyfriend asked worriedly. “How can I help?”

“You stay here,” I said. “I’m going to be OK. I can do this.” And I hauled ass to the bathroom to do some hippie deep-breathing exercises, take some Klonopin, and talk myself down. Fifteen minutes later, I crawled back into bed.

Source: Healthline

“That’s it?” he asked.

“That’s it,” I said. “That’s all.”

And together, we fell back to sleep. Just like normal people.

Original by