Ongoing efforts to reform and improve life in prison so that inmates can be rehabilitated rather than simply punished have resulted in a number of significant changes in recent years.

One of the biggest areas of attention is on the proliferation of problems relating to racism and the widespread presence of gang culture in prison facilities across the US.

While such issues are still rife, campaigners and those responsible for running the prisons themselves have managed to implement processes, policies and schemes intended to minimize them. Here is a look at what approaches and strategies are being deployed today.

Source: The Conversation

Contents

Understanding the history

It is worth noting that while modern audiences might assume that gang culture has always been part of the prison system in the US, it is actually a relatively recent phenomenon.

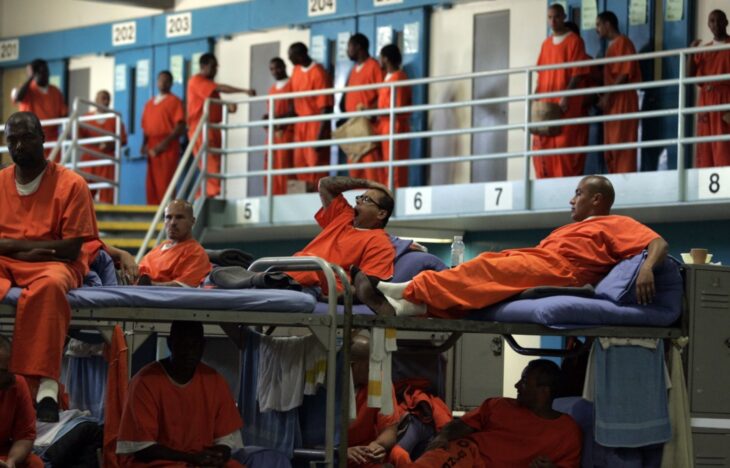

Prior to the 1980s, gangs were not as commonplace as they are today. It was only as a result of the mass incarceration policies introduced and implemented by successive administrations that prisons grew in size, inmate numbers exploded and thus the conditions for gangs to flourish were brought about.

America still leads the world in terms of per-capita incarceration rates, adding to the conundrum further. In short, the more people you imprison, the more likely it is for gangs to form and for the social disparities and prejudices which exist in the outside world to be magnified in this context.

Experts recognize that it is only by examining the historical reasons for the contemporary complications being faced that improvements can be made. There is still a long way to go, but plenty of people are striving for a better future.

Source: Courthouse News

Managing prison populations effectively

Since it is impossible for all racism and gang behavior to be eliminated from prisons, it is more a case that those in charge need to manage the way that inmates mix and step in when it is appropriate to do so.

A search of inmate populations with PrisonRoster’s lookup (in Dallas County in this case) will show that while prisons are generally mixed in terms of ethnicity, racial divides and gang culture go hand in hand, hence the need for proactive orchestration of the social aspects of life behind bars.

In some places, prisoners are prevented from mixing in groups over a certain number, thus dismantling the environments in which gangs might otherwise congregate and grow.

Obviously there are institutional differences in the tactics deployed, but population management principles are regularly being revised and altered to adapt to changing ways of thinking.

Source: Christian Science Monitor

Reducing prison sizes

As mentioned earlier, historically it was less common for gangs to form in prisons in the US because the facilities themselves were smaller and housed fewer inmates. In comparison, the vast prisons that have emerged over the past three decades are largely responsible for allowing gangs to proliferate, while also intensifying the racial divides.

One solution which is being implemented in certain regions is to move away from the mega-prison model and instead house inmates in smaller facilities.

This ties in partly with the population management policies mentioned above, but is about more than just separating inmates into smaller groups to stop gangs forming; it is also about enabling administrators and guards to be more vigilant and effective in their own roles. Rather than barely being able to keep a lid on the conflagration of gang violence and racism in large prisons, those in positions of authority can better fulfill their obligations if there are fewer inmates in their care at any one time.

Source: Los Angeles Times

Structure programs provide a way out of gang culture

It is estimated that around a fifth of prisoners are part of gangs while incarcerated, with around half joining when they are first locked up and the remainder taking across affiliations from their life on the outside.

This means that while it only impacts the minority of inmates, the disproportionate impact on prison violence and racism that this has is something which administrators want to stem through the specific use of exit programs.

While exit programs are more broadly designed to equip inmates with the skills and capabilities that they will need to flourish once they are released back into the freedom of everyday life at the end of their sentences, they are also implicitly organized as a means of helping gang members leave their former affiliations behind them.

Experts recognize that leaving a gang in prison is significantly tougher to do than on the outside, and it is something that requires permission, rather than something that can be done freely at any time.

Counsellors and academic experts on this topic participate in exit programs which stratify the process of leaving gangs in a way that empowers inmates who find themselves in this situation.

Source: The Well Project

Tackling issues in the community

In a sense, by the time that an individual reaches prison, the opportunity to protect them from the worst of the racism and gang culture which are perpetuated within the walls of the average penitentiary has already passed. Even with the campaign work going on and the changes being made, it is too late for those already behind bars, at least in terms of reducing the short term impact of this tricky state of affairs.

To this end, schemes which look to reduce racism and gang culture in the wider community can also be seen as instrumental in shaping how this plays out for millions of people across the country. Crime is very much a community matter, and dealing with its causes rather than simply relying on the penal system to clean up the mess further down the line is clearly the best route forward, and one which a growing number of states are taking.

Ultimately it is recognized that there is no quick fix for the problem of racism and gang culture in prison, but that rather a combination of in-house intervention and prior prevention of the circumstances that lead people to commit criminal acts in the first place will deliver the best results.