I still remember the first time I noticed ringing in my ears: I was 15-years-old and had just gotten home from a concert. My friends and I were sitting around the kitchen table in my parents’ house, rehashing the evening’s events, when I suddenly heard a clear, high-pitched tone, sort of like the noise you hear coming from a television if you listen hard enough. I didn’t think much of it, and by the next morning, the noise was gone. I continued going to shows, pushing my way through crowds to get to the front of the stage — often next to the big stacks of speakers. But it’s a concert, and you want to hear it, and it should be loud, right?

Fast-forward 16 years to just a few nights ago. It’s 2:30 a.m. and I haven’t been able to fall asleep, despite taking a dose of trazodone (an antidepressant that’s also used as a sleep aid) three hours beforehand. The noise in my head — a high-pitched squeal that’s not unlike the sound of a tea kettle — is getting worse the more I worry over not sleeping. The fan and iPhone app that I use for white noise aren’t masking the screech. And this is the second night in a row that I’ve spent hours tossing and turning. As I check my iPhone for the millionth time, hoping that something — reading an article or scrolling mindlessly through Facebook — will help me finally fall asleep, all I can think about is how my stupid brain has ruined my life.

This is what life with tinnitus is like.

Source: Medizinfuchs

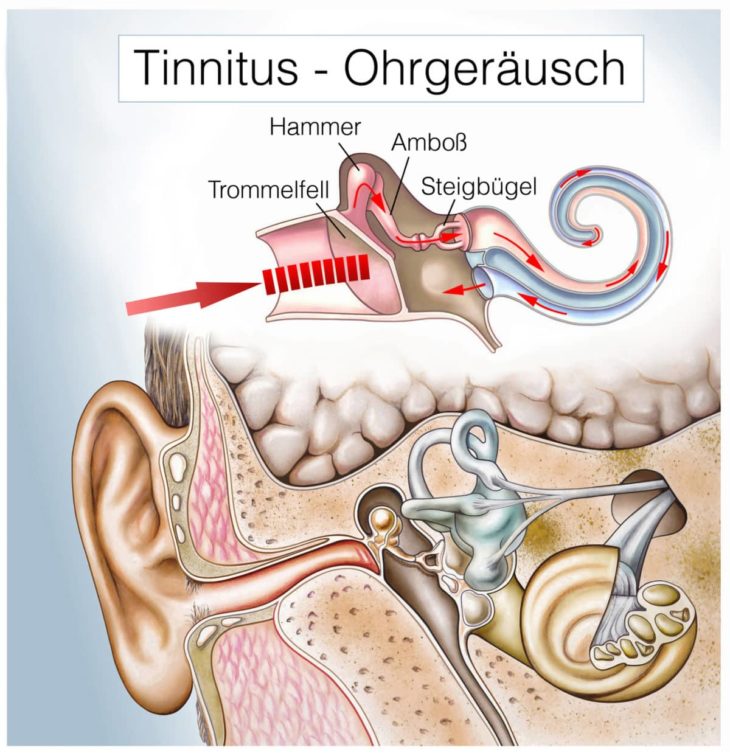

For the uninitiated, tinnitus is defined as “the perception of sound in the ears or head where no external source is present,” according to the American Tinnitus Association. If you’ve ever heard ringing (or a squeal, or any other phantom noise) that no one else can hear, then you’ve experienced tinnitus. Although the most common cause is exposure to loud noise, there are many ways to get tinnitus — it can be connected to sinus issues, medication that you’re taking, or dental problems like TMJ.

For many people, that ringing fades away after a while, either disappearing altogether or becoming virtually unnoticeable. For some, that doesn’t happen. Although it’s estimated that one in give Americans suffers from the condition, the number of people for whom tinnitus is a chronic, severe problem — one that affects day-to-day life — is far fewer. They include military veterans (one of fastest-growing groups of people with tinnitus), musicians, construction workers, and people like me, who never did anything more than go to concerts and listen to music too loud.

The first time my tinnitus flared up, I was 22-years-old. I’d listen to music through my iPod on full blast while riding the subway or during long walks around my neighborhood. But one night, I noticed the ringing as I tried to sleep. And the next night. And the night after that. Finally, two mostly-sleepless months later, I accepted that tinnitus was a part of who I was. Gradually, it lessened a bit, becoming a minor annoyance that could usually be masked by a small fan. And I was more careful, wearing foam earplugs to every single concert I attended, and never listening to headphones so loud that I couldn’t hear ambient noise around me. For nearly a decade, things seemed fine.

But things changed earlier this year, when my tinnitus spiked. I woke up one January morning with a tone in my right ear that was higher-pitched and louder than before, and it hasn’t gone away since. It eventually moved into both ears, with the left one usually being louder. This time, tinnitus affected my life in ways that I never thought imaginable: I’ve seen two ear-nose-throat doctors, both of whom oh-so-helpfully told me I’d just have to get used to the noise. (Which, yeah, I didn’t need a doctor to tell me that.) On the advice of one, I stopped drinking coffee and alcohol for about a month. I wore earplugs on the subway. For a while, I didn’t go anywhere that could possibly be noisy — no bars, no concerts, even comedy shows were out. I became a person that I didn’t quite recognize, fearful of facing the world and bitterly depressed about having a seemingly untreatable health problem.

Source: Agoro

If you’ve never experienced tinnitus firsthand, it may be hard to comprehend the toll it can take on your quality of life. Shouldn’t people suffering from it just be able to tune the noise out? Can’t you just ignore it, or cover it up? It’s not like it’s a serious illness, right? But until you’ve had one of those sleepless nights where a sound akin to a dog whistle is screaming in your head — all while knowing there is literally nothing you can do about it — you can’t really know how infuriating, and batshit-crazy-making, tinnitus can be.

One of the shitty things about tinnitus is that there is no cure; there are only coping strategies, and ways to prevent it from getting any worse. Time helps; people often habituate to the noise after a while, as I did with my first flare-up. But the best thing to do is find ways to distract yourself from the noise, whether through meditation, cognitive behavioral therapy, or different masking methods. It’s generally agreed that stress and anxiety make it worse, largely because they make it difficult to not focus on the ringing. And there are plenty of times when the constant, loud, stupid ringing is impossible to ignore, especially since I’m an anxious person to begin with.

Because there is no cure for tinnitus, it’s easy to succumb to feelings of hopelessness. I think about my life in five, 10, even 50 years, and it’s hard to imagine what it will be like. Will my ears be better or worse? Will there ever be a cure? Will I be able go to concerts, or travel? Even scarier, tinnitus can be a side effect of pregnancy for some women — what happens if I have kids and it becomes too much to handle? Thinking about the possibilities is terrifying, and ultimately counterproductive, but my anxious tendencies lead me down those roads all the time. Those thoughts also lead to insomnia, the absolute worst side effect I’ve experienced. Not sleeping when all you want to do is sleep is fucking miserable. (And sleep deprivation can make tinnitus worse. Great.)

Some things have helped: I have the support of my boyfriend, an infinitely patient person who deals with my 2:30am freakouts (and requests for tea or backrubs) with aplomb. My parents are also there for me, and I have their home to visit if the stress of dealing with tinnitus becomes too much. (I’ve done that twice in the past six months — it helps.) There are still things I can do to manage the symptoms: yoga, acupuncture, different supplements, tinnitus retraining therapy (meant to help your brain adjust to the noise it’s perceiving), and good old-fashioned therapy. I’m actually lucky that my tinnitus isn’t as severe as it could be; I can generally ignore or mask the noise during the day, and I have medication to help me sleep at night when I need it.

As much as it has affected me, and as much as it fucking sucks, I have to remember that tinnitus isn’t inherently life-threatening. The sleep deprivation and the depression that come along with it are difficult, to be sure, but they’re also surmountable challenges. I’ve had plenty of low moments, times when I’ve cried hysterically, or cursed my bad luck, or wished that I didn’t have to be alive to deal with this. But I’m not about to let a stupid trick my brain is pulling on me ruin my life.

Original by Amy Plitt