When I was fresh out of college, I worked at an egg donation agency, which paired egg “donors” with potential parents willing to shell out a lot of money for the possibility of having children. At parties, when I was asked what I did for a living, it was inevitable that a group of girls would gather around, asking questions. Everyone had seen those ads on the bus—“$7,000 to donate your eggs!”—and this was 2018, when the economy was digging itself deeper into a recession. In fact, the whole reason I’d taken this gig was because the egg donation business was booming while there was a serious lack of jobs in my field for recent grads.

It wasn’t rare at these parties that I would get cornered in the hallway by some girl who was drunkenly considering egg donation and wanted to weigh the morality of it with me. Wouldn’t they be, like, my babies out in the world? she’d ask. “Err, yeah,” I’d say, trying to skirt the issue. But on rare occasions, the girl cornering me would be a little less drunk and sound a little more serious about the whole scenario. In those cases, I’d move on to questions like: “How much do you weigh? Have you ever been diagnosed with anxiety or depression?” Surprisingly, these are two of the most important questions in the process.

The thing is, I can’t tell you whether you should donate your eggs. But I can tell you if you could.

At work, it was my job to screen potential donors. In the morning, I would be the first one in the office and the phone would already be ringing. After a few months, I learned not to scramble and get it. I’d take off my coat, unwrap my scarf and prepare to listen to dozens of voicemails left during the Infomercial hours. From what I gathered, 2:00 a.m. is generally the time donating your eggs for money begins to seem like a good idea.

Some of the calls were, for lack of a better word, intense. There were boyfriends talking in hushed tones into the receiver, trying to pimp out their girlfriends’ eggs. When I’d call these guys back, I’d demand to talk to the girlfriend directly, and make sure they understood exactly what their significant other was scheming. More than once, this resulted in a woman screaming “You Motherf***er!” in the background, then hanging up the phone.

Source: Hoerly

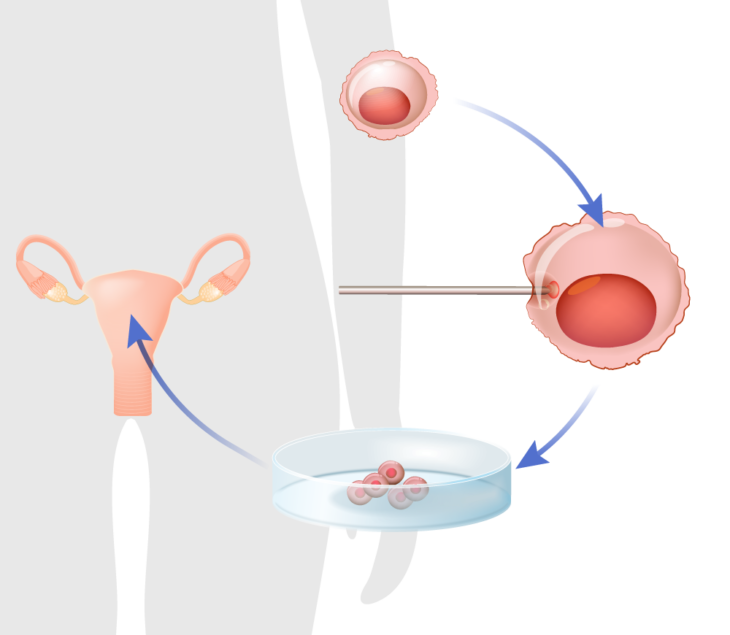

Then there were girls who made it through the initial interview, only to back out after I gave my speech about the vaginal procedure and needles involved.

But most of the voicemails were just left by the “wrong” kind of potential donor. You may have gathered from the ads in the back of your college newspaper, but clinics want specific donors—those who are college educated, tall, and most often white. As one girl said to me during a phone interview, “You just want white bitches.” The world of egg donation is unfortunately not color blind.

Egg donation isn’t a surefire way to have a child. Potential parents pay $20,000 per egg donation cycle—and one cycle does not guarantee pregnancy. Potential parents begin their first cycle by thinking about the genes they most desire—“We need someone who is talented musically,” or “Someone who has a high GPA.” Later though, if the first cycle doesn’t take, they want a proven donor whose past egg retrievals resulted in pregnancy. Seeing how many young, healthy women didn’t become “proven donors” made me paranoid about my own fertility, and it’s a paranoia that has stayed with me over the years.

At parties, when the women inevitably circled up and began digging into whether egg donation was something they should consider, I’d grip my plastic cup tighter trying to parse what I should and shouldn’t tell them. I didn’t want to tell them that weight was the first barrier—you had to be BMI fit. Or that if you’d ever been in therapy you might not get through—and definitely not if you had any past of anxiety, depression or disordered eating. And I really didn’t want to say to my group of progressive friends, “Oh and no lesbians!” It was one of the reasons I would later leave the job, but these agencies apparently still thought there was a “gay gene.” See where, at this party, I could start to sound like a bigoted a**hole?

Generally, I chose to tell people what I told the donors. It was a spiel that left a lot unsaid, bracketed here for the sake of full disclosure: “If you pass the requirements, you are put in the system [where you sit with hundreds of other donors]. When [more likely if] an intended parent chooses you [and this could take a year or more], we’ll call and ask if you can go through a cycle immediately. A cycle involves several early-morning doctor appointments for a month, during which you will get a shot of hormones [which have side effects very similar to PMS]. After a month, you will go through the egg retrieval process, which is done vaginally. You’ll be put out for it, and you’ll wanna take the entire day off and get plenty of rest.”

What it really came down to for most girls at parties, though, was that going through a cycle means drastically changing your lifestyle. You can’t drink for a month. You might gain weight thanks to those hormones. And it’s recommended that you abstain from sex during the cycle—as you will be super fertile for the month. Also, there is some risk of Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) which is very rare, but can be very serious.

Source: Los Angeles Reproductive Center

I was asked to ponder this risk-reward ratio, too. Often, my co-workers would ask, “So when are you going to donate your eggs?” I was torn on the whole issue. For me, it wasn’t the possible side effects or that I was worried about my familial history making donation a no-go. For me, it was more about the whole bringing-a-child-into-the-world thing.

I didn’t fault parents for choosing egg donation over adopting. This was their choice and I understood why egg donation could be so appealing. As I mentioned before, this job made me very paranoid about my own fertility, sometimes resulting in crying bouts to my husband about how much I want a baby someday. In those moments, I understood that if you can’t have a baby yourself, getting the genes of someone you perceive to be most like you could feel like the second best option.

But as I considered selling or donating my own eggs, I began eyeing the potential parents at the clinic with distrust. With the high cost of egg donation cycles, most of them had the monetary means to care for a kid. But suddenly I noticed the potential father who yelled a lot and seemed quite sexist, or the mother who called our office 15 times a day for no real reason other than to sigh at me and ask snippy questions about the donors. Who were these people and how would they be raising my gene-babies? I empathized with these potential parents … but never quite enough to sell them my genes.

As I began closely monitoring these parents, it started to seem like they had babies for selfish reasons. At the same time, I felt selfish, like I was hoarding my eggs. It all seemed like such a strange cycle.

I guess what I’m trying to say here is that, if you are considering donating your eggs, there is an awful lot to think about. It’s not a slam-dunk decision in any way. Still, if I were giving advice to my best friend, I’d say that, if you meet the stringent requirements, go for it—you can donate eggs up to six times and you can even haggle to get more money, especially if you become a proven donor.

But there is one last risk I often think about. What if, 20 years after donating, you get a call from someone who is genetically your baby. I mean, whoever holds my old position at a clinic has access to all the records of who donors are and whose eggs went to whom. If that person is just another kid out of college, who could also use tip money, it feels too easy for this information to get out. Just sayin’.

Original by Rachel White