Ah, testicles. So mysterious! So enigmatic! Why do they look like that? How do they work? The testes are an enigma to most women. Thankfully, an evolutionary psychologist and a pair of female researchers have stepped forward to answer the question: “Yo, what’s up with testicles?” In this month’s Evolutionary Psychology, Gordon Gallup, Mary Finn, and Becky Sammis explain the evolution of the testes. Find out wassup with the sack after the jump!

Why are testes designed the way they are? Smart people in white coats have been scratching their heads over why human testicles descended for years. After all, not all beasts are constructed thusly. For example, elephant testicles are hidden away inside the body, protecting them. Why are human males danglers? One theory is that testicles descended from the body for the purpose of “showing off,” like peacock feathers. In theory, the bigger the scrotum, the greater likelihood of reproductive success.

Source: Andrologist London

Turns out, that’s not the case. If that were true, guys would have grown some really big balls over the years. “[W]e would expect to see scrotal testicles becoming increasingly elaborate and dangly over the course of evolution, not to mention women should display a preference for males toting around the most ostentatious scrotal baggage.” Happily, that’s not what happened.

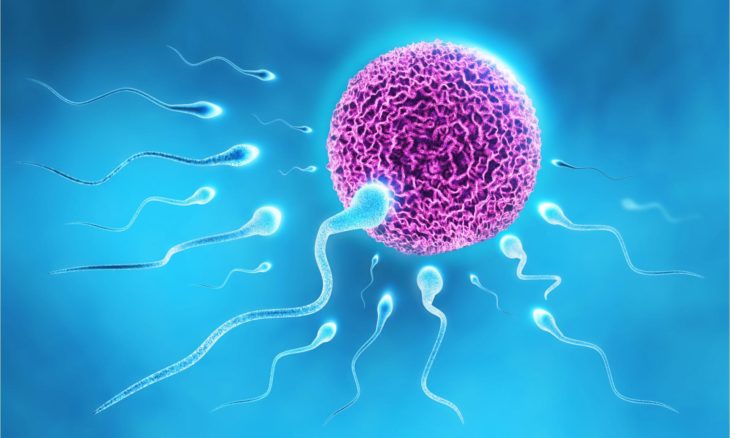

In reality, the scrotum serves as a production facility and “cold storage” for sperm, which likes to chill where it’s coolest. Descended testes keep the sperm cool, moving the happy sack away from the body. The temperature inside the scrotal zone is 2.5 to 3 degrees Celsius lower than the rest of the body. When the chilly semen fridge comes into contact with a vagina, the heat “activates” the exposed testes, “radically jumpstart[ing] sperm that have been hibernating in the cool, airy scrotal sack.”

Source: Medme

It’s only when encountering the vagina that the exposed testicles really get busy, “temporarily making [sperm] frenetic and therefore enabling them to acquire the necessary oomph to penetrate the cervix and to reach the fallopian tubes.”

And dudes thought they were doing it all on their own. [Scientific American]

Original by Susannah Breslin