Over the last 15 months, true crime has seen a surge in popularity and attention amongst a widening audience thanks to the Serial podcast, Netflix’s 10-part docuseries Making A Murderer, and, to a lesser degree, HBO’s The Jinx, which have sought to elevate the genre from cheesy reenactment-filled fluff to high-brow non-fiction storytelling.

All briefly languished in near universal praise before, as has become custom, meeting the inevitable backlash that comes for pretty much every pop culture obsession. While I’ve tuned out the contrarians who make a living “well actually”-ing everything, much of the criticism of this true crime revival, especially those focused on Serial and Making A Murderer, has been frustratingly obtuse and dismissive of the impact they’ve had on shifting public perceptions of law enforcement and the justice system.

The most recently example to make me want to bang my head against a wall is Kathryn Schulz’s op-ed in the latest New Yorker. Schulz argues that Making A Murderer “goes wrong” by “consistently lead[ing] its viewers to the conclusion” that Steven Avery is innocent and was framed by officers from the Manitowoc County Sheriff’s Department, making the series seem “less like investigative journalism than like highbrow vigilante justice.”

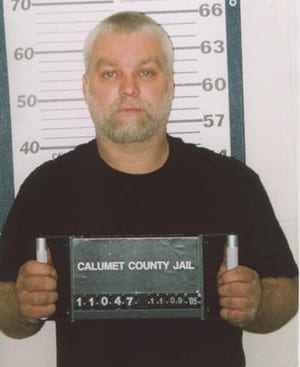

Steven Avery

Both Serial’s first season — about the conviction of Adnan Syed for the murder of his high school girlfriend in 1999 — and Making A Murderer make it clear that they present an alternative point of view on a matter of established legal fact, asking, “Was an innocent man convicted of a murder he did not commit?” In both cases, sharp, engaging, emotionally effective storytelling raises serious doubts about their subject’s guilt, but, far more importantly, they illuminate systemic flaws in the justice system as a whole.

While very different, both series have aided in educating the public about a legal system that would prefer to be regarded as too complicated to understand because our ignorance makes us easier to control. The outrage that these series have inspired is a long time coming. Let’s not diminish or dismiss that (mostly constructive) outrage – a few misdirected tweets notwithstanding – in favor of handwringing and nitpicking over journalistic impartiality. Anything that successfully chips away at the cult-like reverence with which our country treats those who make and enforce laws should be celebrated and encouraged.

*****

Schulz doesn’t quite see it that way, at least when it comes to Making A Murderer. This “private investigative project,” Schulz warns, is an example of the “Court of Last Resort,” which is “bound by no rules of procedure, answerable to nothing but ratings, shaped only by the ethics and aptitude of its makers.”

It’s worth noting, since Schulz does not, that in the Court of Last Resort, the stakes are nowhere near as high as they are in a Court of Law, as any judgments passed are not going to land anyone behind bars or on death row. In the case of both MAM and Serial, that has already happened — at the very most, the Court of Last Resort can only hope to influence the extremely unlikely objective of exonerating the convicted.

Pfft.

Look, I have a journalism degree too, and I believe in the merits of traditional, “unbiased” journalism. However, journalists are still human beings, all human beings have biases, and those biases impact our understanding of what it means to be “unbiased.” Good journalism takes many forms; just as “traditional” journalism is particularly susceptible to failure in the pursuit of balance (assuming there are two valid sides to every story is the reason we entertain climate change denialism, for example), non-traditional journalism (like the “New Journalism” pioneered by, ahem, The New Yorker) can go where “straight news” can’t. Podcasts and documentaries are not traditional journalism.

Making A Murderer’s filmmakers Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos claim to done a thorough job of presenting the State’s most compelling evidence of Avery’s guilt. Prosecutor Ken Kratz, arguably the most reviled figure in the series, was asked to participate and he refused. He has since complained in various interviews that MAM omitted key evidence, including testimony about Avery’s alleged preoccupation with Halbach, and the fact that “investigators found DNA from Avery’s perspiration on the hood latch” of Halbach’s car.

But that means the defense’s cross-examination of that evidence was omitted from the documentary as well. Schulz accepts Kratz’s interpretation of this evidence as fact, then asserts that this “sweat DNA,” as Kratz calls it, would have been “nearly impossible to plant.”

So yeah, the “sweat DNA” is hardly compelling evidence of Avery’s guilt, and it’s doubtful that the full picture of this evidence would have swayed many viewers’ opinions. Schulz wants us to believe the omission is a willful attempt to mislead the audience, but it certainly doesn’t undermine all the other evidence the series presents.

*****

Throughout her piece, Schulz makes direct comparisons between the “egregious” police and prosecutorial misconduct shown in MAM to the flawed choices made by the filmmakers themselves, even suggesting that their underlying motivations are the same. She writes:

The vast majority of misconduct by law enforcement is motivated not by spite but by the belief that the end justifies the means—that it is fine to play fast and loose with the facts if doing so will put a dangerous criminal behind bars.

That same reasoning, with the opposite aims, seems to govern Making a Murderer. … Ricciardi and Demos … stack the deck to support their case for Avery, and, as a result, wind up mirroring the entity that they are trying to discredit.

But Ricciardi and Demos’s “stacked deck” is not playing the same game, or with the same stakes, as the justice system.

“Traditional journalism,” if that’s what we’re calling it, takes the authorities’ accounts at face value, and presents a false balance between the two sides. But that information is often misleading, manipulative, inflammatory, prejudicial or, in some cases, straight up inaccurate — and then rarely corrected. Pre-MAM, Avery was treated as unequivocally guilty and the media’s coverage of the case perpetuated the flaws in the system and poisoned the jury pool. “Traditional journalism” misrepresented the strength of the state’s case, and fell victim to Katz’s manipulation.

This is one of the ways in which the deck was stacked against Avery/Dassey. An Avery trial juror recently told In Touch that the jury found Avery guilty of “raping and torturing” Halbach, referring to the scenario laid out in Dassey’s retracted confession. But Dassey’s confession was never presented at Avery’s trial — it did, however, get plenty of airtime on the local news thanks to a press conference held by prosecutor Kratz months before. In other words, the jury apparently allowed inadmissible prosecutorial propaganda to influence their verdict — that’s far more concerning to me than allegations a documentary downplayed Avery’s criminal history and left imaginary “sweat DNA” on the cutting room floor.

Does Schulz really want to argue that MAM’s biases have done equal or greater damage in the opposite direction? That over 10 hours, MAM misrepresents the facts to an extent that other media hadn’t?

Ultimately, no matter what the response to Making A Murderer, or how many signatures are on a Change.org petition calling for a pardon, it’s going to take much more, namely new evidence or new scientific advancements, for Avery or Dassey to have even the tiniest shot at being exonerated. The support of the Court of Last Resort unfortunately doesn’t make the fight for freedom any easier.

*****

There is no better evidence of this than the case of the West Memphis Three and the HBO documentary trilogy Paradise Lost, which Schulz lists among the “standouts” of the true crime genre, despite the fact that it is far more similar to Making A Murderer than Serial in terms of making a case for the convicted’s innocence.

In 1993, Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley were tried and convicted in the murders of three eight-year-old boys in rural Arkansas; Echols, 18 at the time of his arrest, was sentenced to death, while Baldwin, 16, and Misskelley, 17, were each sentenced to life in prison. The filmmakers began work on the first Paradise Lost after seeing a New York Times story about the investigators’ belief that the teenagers killed Steve Branch, Michael Moore and Christopher Byers as part of a Satanic ritual. The film was released in 1996, and they continued to document the West Memphis Three’s fight for freedom in two followup documentaries released in 2000 and 2012.

The presentation of the police investigation in Paradise Lost is not dissimilar from what we see in MAM. West Memphis police coerced a false confession out of Misskelley, who had an IQ of 72, and he implicated Echols (who the police already had marked as their lead suspect) and Baldwin; Misskelley eventually retracted his confession, and all three maintained their innocence. Misskelley refused to testify against the other teens, so he was tried separately and his confession was not used in the State’s case against Echols and Baldwin. Despite a disturbing lack of physical evidence that tied any of the three to the murders, West Memphis prosecutors used dubious “expert” testimony to successfully convince the jury that Echols – who wore a black trench coat, listened to heavy metal, dabbled in paganism and was an all around “weirdo” by early-‘90s Bible Belt standards — was a devil worshipper who acted as the ringleader for this heinous crime.

Lorri Davis was a landscape artist living in New York City when Paradise Lost came out in 1996. She was deeply affected by the film and found herself being unable to think of anything else.

“While Paradise Lost certainly led me to believe in Damien, Jessie and Jason’s innocence, I don’t think it’s edited in a way that allows no doubt,” Davis told me via email. “I did a great deal of research on the case after I saw the film, and it wasn’t easy to do back then. The internet was fledgling, so I had to go to the courthouse to obtain the documents. I read everything I could get my hands on. “

Feeling a particular affinity towards Echols, she sent him a letter, the first of thousands exchanged between the two while Echols was on death row (a collection of those letters, Yours For Eternity: A Love Story On Death Row, was published in 2014). They fell in love, Davis moved to Arkansas and they were married in 1999; their wedding day was also the first time they were permitted to touch. At that point, Echols’ case was at a virtual standstill, but Davis was Echols’ fiercest advocate and she made fighting for his exoneration her full-time job. Both she and Echols credit the Paradise Lost series for spreading awareness about the case, which led to support and resources, including from people like Johnny Depp, Eddie Vedder, Henry Rollins, and Natalie Maines from the Dixie Chicks.

Paradise Lost also brought the case to director Peter Jackson’s attention, and for years, he and his wife Fran funded a private investigation, hiring some of the country’s leading forensic experts to re-evaluate the case. Crucial new DNA evidence and new witnesses were uncovered as a result of those efforts, and in 2010, the Arkansas Supreme Court finally decided to reopen the case. In 2011, Echols, Baldwin and Misskelley each agreed to enter an “Alford plea” – which is technically a guilty plea that allows the accused to assert their innocence – in exchange for time served. The plea was accepted and on August 19, 2011, after more than 18 years in prison, the West Memphis 3 were released.

“There is absolutely no doubt that the pressure from supporters brought upon the State of Arkansas had a huge impact on their actions,” Echols said. “They knew they were being watched, and those dealing in corruption don’t like a spotlight. You can have all the evidence in the world proving your innocence and they will still kill yon and sweep it under the rug to keep from admitting they made a mistake. The other half of the fight is getting word to the public.”

“Paradise Lost provided an actual window into the courtroom,” Echols explained. “The audience can see and hear the exact information as it was being played out in court. It is a powerful take on how the process can actually go so horribly wrong.”

The film also served as a counter to how “traditional journalism” had covered the case.

“The local and national media were operating from a sensational standpoint,” Echols said. “They reported what the police were telling them — the Satanic rumors and Jessie’s confession led to a media feeding frenzy.”

Echols has seen Making A Murderer and, as he wrote in an essay for the AV Club, was “haunted by the parallels” to his own life. But he’s also clear that his case and Avery’s case are not outliers.

As in my experience, it was a team of filmmakers who shined the light on his case and the heinous actions of those involved in the criminal justice system. And as in my case, people from all over the world are coming forward and acting, demanding that this total disregard for justice be righted.

People have told me over and over that my story is unique, the circumstances of my case—the injustice to the real victims, their families, to the West Memphis Three—made for a perfect storm, never to be seen again. But lightning does strike twice, and many more times after that—my story and Steven’s are only two in the vast, impenetrable legal landscape.

Echols regards the criticism that MAM left out key evidence with some suspicion – just consider the source.

“The filmmakers should tell the truth to the best of their ability,” Echols said. “But the tricky part is that once police, prosecutorial or judicial corruption has been proven, it’s hard to discern whether or not [this] evidence pointing to guilt is actually real. After all, it’s the prosecutor making the allegations – the same prosecutor [Ken Kratz] who was provided an opportunity to present that evidence to the documentarians and turned it down.”

Regardless, for Echols, Avery’s guilt or innocence is beside the point.

“The most important aspect of [Making A Murderer and Paradise Lost] is that they uncover the corruption in the cases they study,” Echols said in his email. “If corruption exists, the justice system has failed.”

*****

“Playing fast and loose with the facts” led West Memphis officials to not only nearly execute an innocent man, but it allowed the real killer of three eight-year-old boys to get away with it. While Echols, Baldwin and Misskelley have been freed, they have not been exonerated, and Arkansas still considers this an open and shut case.

In her New Yorker piece, Schulz expresses valid concern that these true crime documentaries “turn people’s private tragedies into public entertainment,” causing further pain to the victims’ loved ones. The question is whether the “demands of private grief are outweighed by the public good” – do the ends justify the means?

But what about the pain experienced by those who have been wrongfully convicted, even executed, for crimes they did not commit? What about their loved ones’ grief? What about the pain inflicted on the parents of Steve Branch, Michael Moore, Christopher Byers, and other victims whose killers were never caught because police went out of their way to pin it on someone else?

Pam Hobbs, the mother of Steve Branch, and John Mark Byers, the stepfather of Christopher Byers, were once convinced of the West Memphis 3’s guilt. But their minds were changed by what the Paradise Lost films revealed about the police investigation, and by the third film, Byers especially was an outspoken advocate for their release. (Both Hobbs and Byers also attended the Sundance premiere of West of Memphis.) While I can only imagine how painful it must have been to relive this tragedy not just once, but over and over again as the films were released, the real travesty is that a documentary did more to seek justice for their children than West Memphis law enforcement.

The various arms of the criminal justice system have tremendous authority to detain, to arrest, to imprison and to kill; when they play fast and loose with the facts to accomplish those goals, ALL of our most basic of rights are being threatened. We all suffer. Do those ends justify the means?

*****

Unlike MAM, Serial never directly or indirectly alleged police or prosecutorial misconduct, and host Sarah Koenig tiptoed around taking any significant positions, including on Syed’s guilt. Schulz may have preferred Serial’s “intellectual and psychological oscillation” to what she calls MAM’s “certitude,” but many listeners were left unsatisfied in the end. While I didn’t expect Koenig to pronounce Syed guilty or innocent, I was disappointed by how tacitly accepting she was of the police’s investigation.

Throughout the months of listening to Serial, I, like many others, tried to come up with alternate theories of my own. If Adnan Syed didn’t kill Hae Min Lee, who did? The trouble, of course, is that an even bigger question loomed – If Adnan didn’t kill Hae, why did Jay Wilds say he helped Adnan bury the body?

Naturally, many of those who believed in Syed’s innocence suspected that Wilds, the State’s key witness, killed Lee and framed Syed for the murder. The police and prosecution were clearly willing to work with him – though he confessed to A) knowing about Syed’s plan to murder Lee in advance and B) helping him bury her body, Wilds was never prosecuted for his role, accepting a plea agreement in exchange for his cooperation and testimony. A pending charge for disorderly conduct was also wiped from his record.

What Serial never really considered was the possibility that Wilds lied not just about Syed’s involvement, but his own. What about the possibility that Wilds’ confession was entirely false? Unlike, say, Jessie MissKelley or Brendan Dassey, this confession didn’t result in any sort of punishment – but recanting that confession and admitting that he perjured himself likely would, especially because of his plea agreement. Before Wilds’ first official taped interview, the cops did a three-hour “pre-interview” – what was said, we will never know. But Wilds’ ever-changing narrative is ultimately what led me to consider the possibility that he had falsely confessed and that the police then fed him information about the crime in order to make his story fit their facts. Hell, Wilds’ story is still changing. In an interview with The Intercept last year, he introduced an entirely new timeline from the one presented at trial. Oops.

When I suggested to a friend that neither Syed or Wilds was involved in Lee’s murder, but that the police believed Syed was likely guilty and played “fast and loose with the facts” to ensure a slam dunk case, he scoffed. “The police only lie to protect themselves,” he said dismissively. “And why would Wilds confess to something he didn’t do? That’s crazy.”

It may seem crazy, but it’s actually pretty common. As Schulz notes:

Seventy-two per cent of wrongful convictions involve a mistaken eyewitness. Twenty-seven percent involve false confessions. Nearly half involve scientific fraud or junk science. More than a third involve suppression of evidence by police.

That Serial’s “intellectual and psychological oscillation” never addressed statistics like these, despite its focus on a possible wrongful conviction, points to its own bias towards trusting the justice system and upholding the status quo. Cops only lie to protect themselves. People don’t confess to crimes they didn’t commit. The investigation happened exactly as the cops say it did. I’m not suggesting that Serial needed to throw around accusations of police misconduct all willy-nilly, but ignoring the possibility of a false confession or witness coercion makes it less complete than MAM.

Serial’s investigation may have been somewhat shallow, but it still did have a direct impact on Syed’s current appeal. During the course of her investigation, Koenig was able to locate and speak to a key alibi witness that had seemingly eluded the defense; that witness, Asia McClain, then filed an affidavit claiming that she was actually dissuaded from testifying at Syed’s post-conviction hearing by the prosecutor, Kevin Urick. (Urick denies this.) With McClain back in the mix, Syed’s quest for an appeal became more optimistic.

Even bigger developments have occurred in Syed’s case since Serial ended and others picked up where Koenig left off. The podcast brought Syed’s case to lawyer Susan Simpson’s attention and she began delving into the evidence herself, blogging about her findings. She eventually launched an unaffiliated spinoff podcast called Undisclosed, cohosted by Colin Miller, a lawyer and evidence professor, and Rabia Chaudry, a lawyer and family friend of Syed’s who brought the case to Koenig’s attention. Undisclosed went where Serial would not by investigating the investigation itself.

It wasn’t long before Simpson uncovered a bombshell: the cellphone tower data, which was used to corroborate the timeline provided Wilds, was not only unreliable for determining locations on incoming calls, but a fax coversheet from the mobile provider who supplied the data made this point very clear — and yet that essential caveat was withheld from the defense (a potential Brady violation), as well as the State’s own cell tower expert, who now says that information would have changed his testimony. In his interview with The Intercept last year, Urick admitted that Wilds’ testimony by itself, or the cellphone evidence by itself, would “probably not” have been proof of Syed’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

When Syed’s defense team submitted their motion to reopen the case so that McClain could finally testify, they also argued that they should be allowed to present this new evidence of the cell tower data’s reliability on the grounds that even the prosecutor says that the State did not have a strong evidentiary case without it. The request was granted, and Syed’s petition to reopen the post-conviction proceedings was approved based on these post-Serial discoveries.

“The two reasons this case was reopened were based upon the investigations of people doing podcasts,” Colin Miller told me. “More generally, these podcasts and documentaries show that there’s reason to distrust the validity of certain kinds of scientific evidence and there’s reason to question the infallibility of the police and prosecutors. My big hope is that people who are exposed to this, who eventually become jurors, are able to more critically assess what they’re seeing in the courtroom than they might have otherwise.”

Fifteen months ago, Syed’s appeal was at a standstill. Early next month, at a three-day hearing in Baltimore, McClain will finally testify, while Syed’s defense team will also be able to present this new evidence about the reliability of the cellphone data. For the first time in nearly 17 years, there’s more than a glimmer of hope that Syed will be granted a new trial — and maybe even see his conviction thrown out entirely.

*****

Then there is the charge that compelling true crime reporting has emboldened thousands of armchair legal experts to come together — often in the bowels of Reddit — to crowdsource these investigations, the implication being that this is a bad thing. It is hard to take anyone with the username “uricksuxballz” very seriously, I agree, and I don’t condone the harassment of private citizens associated with these cases.

However, I won’t be dismissive or disparaging of these signs that the public is engaged in learning about how the justice system “works.” You don’t have to have committed a crime to suddenly find yourself in deep legal shit, and trust that police and prosecutors exploit our collective ignorance to their advantage. While binging on Serial and Making A Murderer is hardly the same as a law degree, fans of these series know more about how crimes are investigated and prosecuted, not to mention their own rights in these situations, than they did before tuning in. MAM, Serial and Undisclosed have managed to penetrate the thick skulls of people who have otherwise trusted that “the system mostly works,” forcing them to recognize how it can go terribly, terribly wrong.

Bob Ruff is a 16-year veteran firefighter from Michigan and the host of the Truth & Justice podcast. Formerly known as Serial Dynasty, Ruff started the show so he could talk about Serial and his various theories on the Syed case.

“It was really meant to be an outlet for people like me that were so engrossed … that we had notes on our phone and notepads everywhere and all these thoughts with nothing to do with them,” Ruff said in a recent interview. “It was kind of an outlet and a place to put those ideas.”

Ruff not only parsed the evidence presented by Serial and Undisclosed, he also began doing his own digging into the case. Convinced at that point of Syed’s total innocence, Ruff’s goal for the podcast shifted to seeking justice for Lee and finding out who really killed her. By the summer, he had “actually started making some traction in the case that was actually meaningful,” like discovering evidence that Lee’s boyfriend Don falsified his alibi for the day of the murder.

But the bigger bombshell for Ruff was learning just how common false convictions are, as well as the role police and prosecutorial incompetence, negligence and misconduct plays in sending innocent people to prison – and keeping them there.

“When somebody gets arrested and they’re convicted, especially for something like murder, once they’re behind bars, the process of trying to get them out because mistakes were made is nearly impossible,” Ruff said in an interview. “There are programs like the Innocence Project that do a lot of great work in this field, but what I’m doing … is to continue to find these cases, bring them to the public’s attention, try to investigate them using the large audiences that we have as a crowd source to find legal representation and legal remedies and fight for these people who can’t fight for themselves anymore.”

Ruff means what he says. He took an early retirement and as of this month is “advocating for wrongful conviction cases full time.” He’s investigating the alleged wrongful conviction of Kenny Snow in Tyler, Texas, and the case is the primary focus of his podcast’s second season. Ruff expected to see some impact on his audience numbers now that the show isn’t focused on Syed, but he told me that he’s seen less of a drop than expected.

“I assumed that the numbers would fall and then we would rebuild with a more diverse audience that is interested in systematic reform,” Ruff explained over Twitter DM. “I lost about 50,000 listeners, but have already recovered about 30,000.” He estimates that he has about 150,000 listeners.

*****

The justice system has many, many failings, including the fact it is inherently racist, with people of color suffering disproportionately from police/prosecutorial misconduct, not to mention police brutality. That a podcast about a 15-year-old murder or 10-hour Netflix binge has had more of an impact on some white citizens than the police killings of Black men, women and children – like Michael Brown, Rekia Boyd and Tamir Rice – is not lost on me.

Why didn’t a documentary like The Central Park 5, about the wrongful conviction of five teenage boys (four Black, one of Hispanic descent) for the brutal rape of a jogger in 1989, not inspire this kind of outrage? In that case, four out of the five juveniles were coerced by police into making false confessions they later recanted, and the documentary presents evidence that the police should have connected Matias Reyes, who eventually confessed to the crime in 2002, to the case right away. Even after DNA evidence “identified Matias as the sole contributor of the semen found in and on the rape victim,” the District Attorney refused to fully exonerate the five who were convicted for the crime. Instead, the State withdrew all the charges, did not seek a retrial, and had the convictions vacated (which is essentially like saying the trial never happened.)

The problem is also largely one of class, and poor people of all races are victimized by our broken justice system. If some people need to see injustice against a white defendant to begin their deprogramming, so be it. We’ve got to start somewhere. At least some of these people will go on to learn about cases like the Central Park Five, and become woke to racism’s role in our criminal justice system. (If you have not seen The Central Park Five, stop reading and go watch it immediately. Schulz didn’t include it as a “standout” of the true crime genre, but trust me – it is.)

This impact is ultimately why I really just can’t give a shit if Serial or Making A Murderer are biased or even emotionally manipulative.

Frankly, maybe we need to be emotionally manipulated to bring us back to a state of rationality, sanity and empathy. After all, we’ve already been manipulated into believing police officers are saints who can do no wrong, that any harm caused by someone with a badge is either a mistake, somehow justified or the work of a bad apple. We’ve been indoctrinated into believing that with rare exceptions, the justice system works, that everyone is equal in the eyes of the law, and that every citizen’s right to a fair trial, regardless of their innocence or guilt, is one that is respected and attended to by those empowered to do so.

We’ve bought into the belief that police officers and prosecutors are motivated solely by public service, that finding out the truth and seeking justice on its behalf is the only priority – not meeting quotas, sticking charges, winning cases and moving up the chain of power by any means necessary. And this blind belief has persisted despite mountains of evidence to the contrary, like:

- the ever-growing list of unarmed citizens, specifically people of color, who have been brutalized and murdered by police officers;

- the lack of any action, let alone legal action, taken against the vast majority of those officers;

- the fact that men who commit sexual violence and rape are rarely prosecuted because they are difficult cases to prove in a society which commodifies female sexuality (and yet the deafening roar of those who insist that real rape victims would and should report persists, as if cops, lawyers, judges and juries are immune to the effects of rape culture);

- the financial blow dealt by the fight to prove one’s innocence, which makes it clear that the best defense is a bank account with a lot of zeros;

- statistics which indicate that at least 2.3-5 percent of those who are currently in prison in the U.S. and four percent of those who have been sentenced to death are innocent;

- and the inhumane treatment of those who are incarcerated, who are offered little in the way of rehabilitation and medical care, and are used as slave labor for privatized institutions.

Sobering statistics like these make their way into the last chunk of Schulz’s article, and while she acknowledges that the police and prosecutorial misconduct seen in Making A Murderer is common, I don’t quite believe that she believes it — or takes it all that seriously. Schulz criticizes Making A Murderer and Avery’s supporters for being “more concerned with vindicating wronged individuals than with fixing the system that wronged them,” yet she ends her piece by rationalizing that our “real courts” with their “broken rules” are preferable to the Court of Last Resort being bound by no rules at all.

And with a shrug, Schulz upholds the status quo by dismissing those who are willing to question the system because they did so imperfectly and without exact solutions. To argue that MAM’s biases and the outrage they’ve inspired do equal or greater damage than the system itself is a fallacy that serves only to squash dissent. That kind of attitude will certainly get us nowhere.

Original by Amelia McDonell-Parry @xoamelia